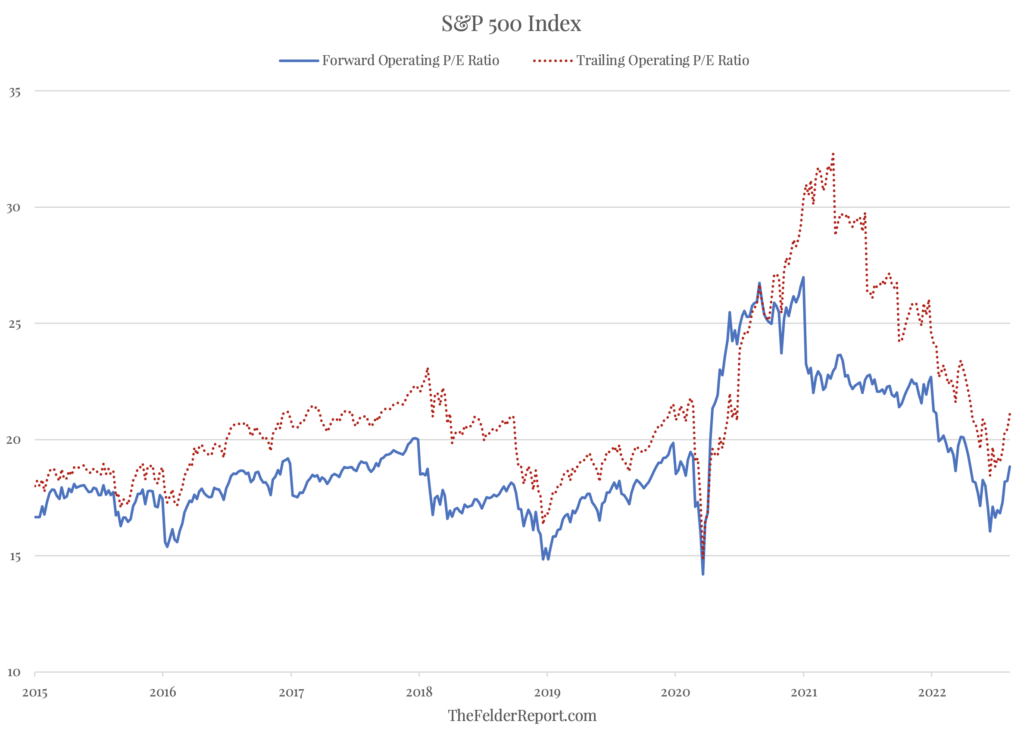

Many investors like to use price-to-earnings ratios as a short-hand valuation tool for both individual equities and the broad stock market. Most of the time this can be useful but there are also times when it can be very misleading. Typically, those times are at the top or the bottom of the earnings cycle.

When earnings are unduly depressed due to recession or are over-inflated due to opposite economic circumstances, the denominator in the ratio is no longer representative of sustainable earnings potential. As a result the metric itself appears dramatically elevated at the bottom of the cycle or somewhat depressed at the top of the cycle, sending a false signal regarding value.

Today, the S&P 500 Index sports a price-to-earnings ratio of 21 on trailing 12-months’ operating earnings and 18 on analyst estimates of operating earnings over the next 12 months. Relative to the past five years, these levels are about average, leading many investors to the conclusion that stocks, after their decline so far this year, are now fairly valued.

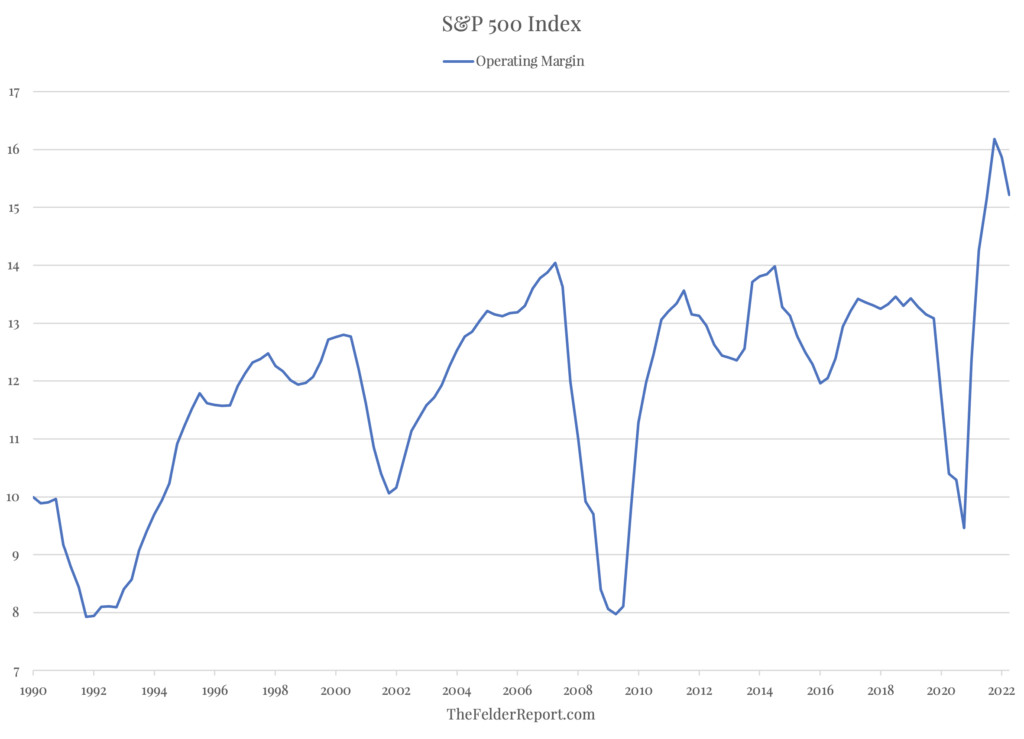

However, it’s crucial to note that the profit margins underlying those earnings currently sit at their highest levels in decades (if not in history). Those price-to-earnings ratios then are only valuable to the extent that extremely elevated profit margins are sustainable. Because if profit margins fall, it will quickly become apparent that earnings were over-inflated and thus price-to-earnings ratios were misleadingly low.

As my friend, John Hussman, points out (and small businesses have been suggesting for months now) there is a compelling case to be made that this is precisely the case. Labor costs have been surging. Typically this puts a great deal of pressure on profit margins but it has not exerted its normal effect as of yet thanks to massive pandemic subsidies. Going forward, though, it’s likely this relationship reasserts itself and profit margins normalize, a risk today’s price-to-earnings ratios don’t reflect.