Michael Burry, of The Big Short fame, recently called passive investing a bubble. I would agree it’s probably a bubble but, more importantly, it’s a mania that has contributed to a bubble in the stock market.

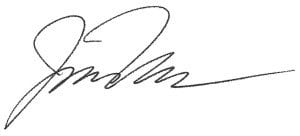

It’s important to distinguish between these two terms. To me, a “bubble,” as Jeremy Grantham defined it, is a move that takes valuations more than two standard deviations away from their long-term average. Mathematically, a move of this magnitude should only happen about 5% of the time in markets. A “mania,” on the other hand, is defined as excessive enthusiasm. I would take it a step further and suggest that a mania in the financial markets is marked by excessive enthusiasm that leads to belief in the impossible that allows for a bubble to form.

Based on our definition of a bubble, it’s clear that the stock market met this criterion back in 2000 and meets it again today:

Twenty years ago the mania that drove prices to bubble territory was the false believe that it didn’t matter what prices investors paid for fast-growing internet stocks; so long as they bought in before it was too late they would certainly make a fortune over time.

Today, the mania driving prices to bubble territory is the false belief that it doesn’t matter what price investors pay for equities via passive funds; so long as they hold on they will be entitled to the historical rate of return and, if prices ever decline, they will always come back. Of course, and probably more importantly, there’s also a mania on the part of corporate managements focused on stock buybacks based on the false belief that what’s good for shareholders in the short run is the most important thing.

The false belief in 2000 was disabused when the Nasdaq 100 Index fell 80% in just 30 months and the majority of the most popular dotcom stocks went to zero.

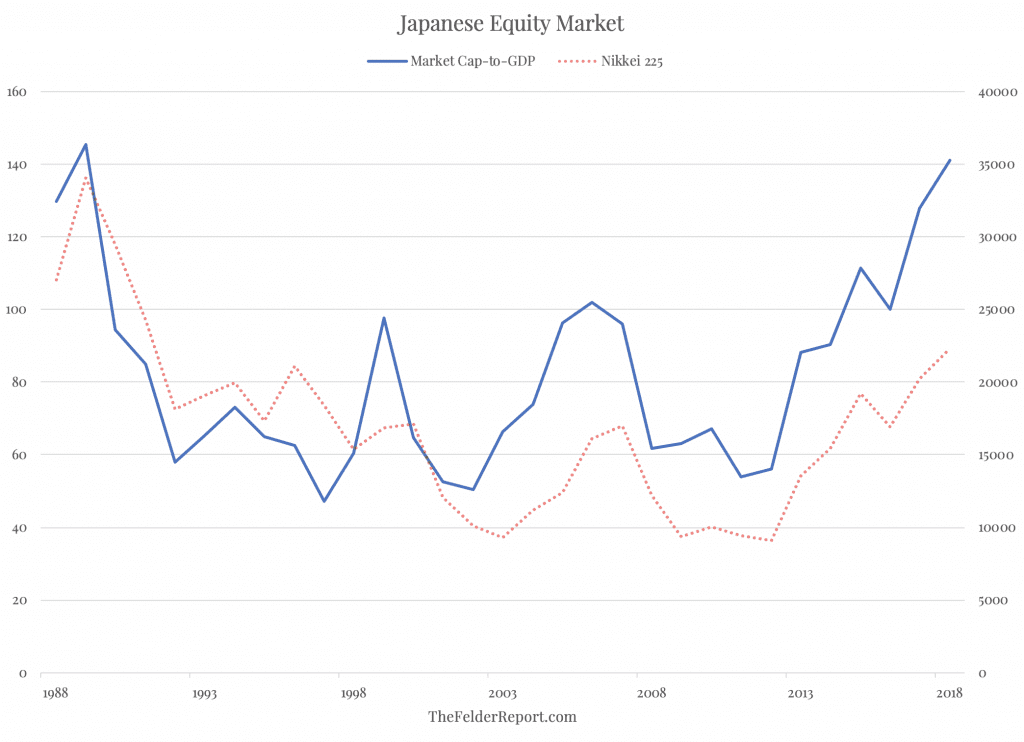

My fear is that for today’s false belief to be disabused it may require a much more protracted decline than either of the bear markets we have witnessed since the peak of the dotcom mania in which prices many years from now remain below today’s highs. For investors to learn that stocks don’t always come back and for management teams to learn that hollowing out the balance sheet to boost the stock price in the short run is detrimental to the long run health of the business it may require a Nikkei-post-1990-type of scenario.

After hitting 140% of GDP back in early-1990, the value of Japanese equities, as measured by the Nikkei 225 Index, remains more than a third lower than the peak it put in nearly thirty years ago (even though valuations are back to those highs).

Is it so hard to believe that, after the U.S. equity market hit 140% of GDP this year, that the S&P 500 could suffer a similar fate? Of course it is, we’re in the midst of another mania and there is only room for belief in the impossible.