There is a growing chorus surrounding the topic of stock buybacks and whether they should be banned. Most recently, Chuck Schumer and Bernie Sanders wrote a piece for the New York Times arguing that buybacks are nothing more than corporate self-indulgence that leads to long-term harm to both companies and the economy. This may be true and, with equity valuations at or near all-time highs, buybacks certainly appear uneconomic at current prices but this is no reason to ban them. Companies should be allowed to throw money down the drain if they so choose. It’s a free country, as they say.

That said, there is a very good reason for banning buybacks and it’s the very same reason they were banned for decades before the Reagan administration allowed them to recommence in 1982: They are nothing more than stock manipulation on a massive scale.

As John Authers recently pointed out, “For much of the last decade, companies buying their own shares have accounted for all net purchases. The total amount of stock bought back by companies since the 2008 crisis even exceeds the Federal Reserve’s spending on buying bonds over the same period as part of quantitative easing. Both pushed up asset prices.” Let me rephrase that: there have been essentially no other buyers of equities over the past decade besides the companies themselves and they’ve spent over $4 trillion at it, even as liquidity has fallen to record lows.

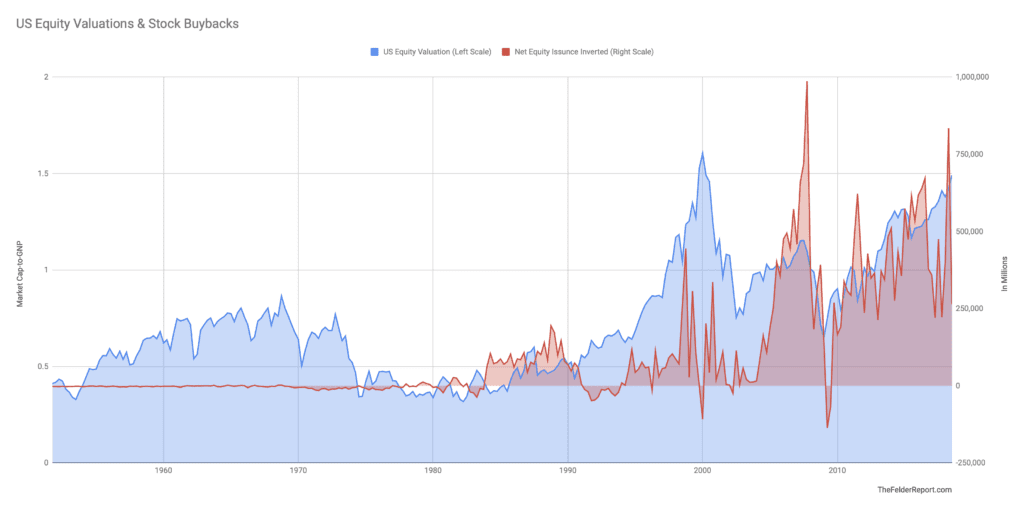

So it’s not hard to understand how valuations have gone to the moon. Without that $4 trillion in stock buybacks and in a market where trading volume has been falling for decades they never would have been able to soar as high as they have. The chart below plots “The Buffett Yardstick” (total equity market capitalization relative to gross national product) against total net equity issuance (inverted). Since the late-1990’s both valuations and buybacks have been near record highs. Is this just a coincidence? Considering all of the above I think it’s safe to say it’s not.

The question then becomes why would management seek to inflate the valuation of their firm’s equity? The answer is very simple. As the Financial Times recently put it, “Corporate executives give several reasons for stock buybacks but none of them has close to the explanatory power of this simple truth: Stock-based instruments make up the majority of their pay and in the short term buybacks drive up stock prices.”

This is not just an inference made from the clear incentive executives have to fatten their own pockets. Harvard Business Review recently noted there is a statistical relationship between equity-based pay and buyback activity: “We find that the more vesting equity the CEO has in a given quarter, the higher the likelihood is of both buybacks and M&A. Like investment cuts, buybacks and M&A could be good rather than bad — but we find that vesting equity leads to the bad type.”

In addition, the Roosevelt Institute found another curious statistic: “In the first 8 days after a buyback announcement, insiders sell an average of $500,000 worth of stock per day—a five-fold increase as compared to the normal daily average of $100,000.” So the history of buybacks over the past several decades show that they are implemented when executives would most benefit from juicing the stock price and they take full advantage by selling heavily back to their own company.

If this isn’t stock manipulation, I don’t know what is.

Now I’m sure there are shareholders who would be unhappy with my criticism in this regard as they feel they have benefited alongside management during this time. That may be true in the short run. Manipulating the stock price certainly feels good to existing shareholders while it’s happening. However, repurchases made at prices that are uneconomic are damaging to the long-term health of the company.

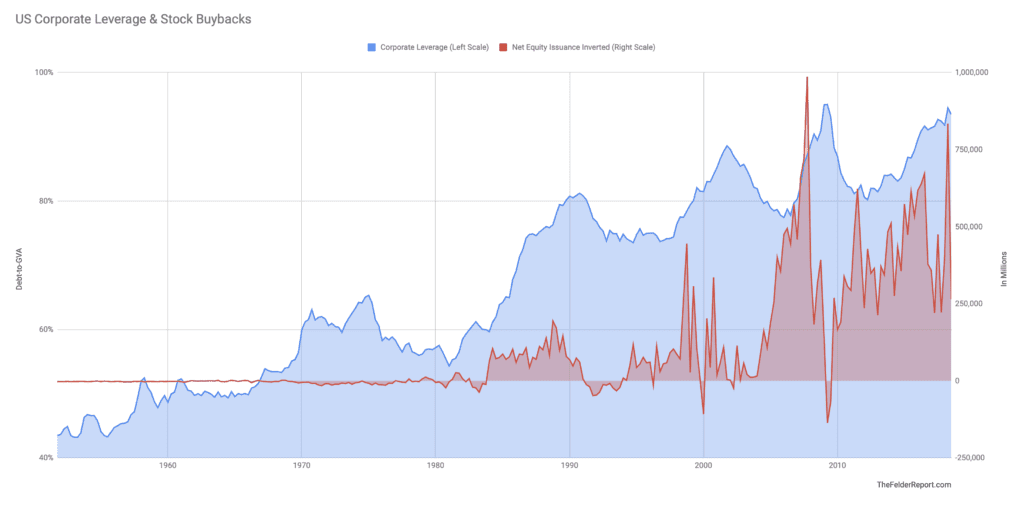

Here again, history (and the chart above) shows that stock buybacks are pro-cyclical. Companies repurchase far more shares at peak valuations and then they halt buybacks altogether, or worse, issue shares when valuations are at their lows. As HBR puts it, there is just too much incentive for the “bad type” of stock buybacks – those that benefit execs in the short run and harm investors in the long run. What’s more, this cycle has seen the greatest amount of debt-financed buyback activity in history. Executive teams have leveraged up their companies to record levels while paying record valuations. As my friend John Hussman put it, corporate executives have, “quietly placed investors on margin.”

The bill will not come due for all of this leveraged equity manipulation until the next recession and concomitant credit crisis. And considering the size the of the leveraged buyback party executives have thrown over the past decade I think it’s safe to say the hangover is going to be just as riotous, though not in a celebratory way. At that point shareholders will be made painfully aware of the true cost of inebriating their upper managements with massive equity compensation and then giving them the keys to the financial car.

The good news is there is a very simple fix here. Stock buybacks in the open market should be banned because they are clearly the single greatest form of market manipulation that exists today. However, this would not preclude companies from putting together tender offers for their own shares. The difference between open market repurchases and a tender offer is night and day. Restricting companies to making tender offers would eliminate the ability to manipulate prices at the discretion of executives. Yet it would still provide a way for companies to deploy capital as they see fit and in a way that is much more forthright and fair to everyone involved.

Clearly, the rationale behind the original ban on stock buybacks was valid. The history of buybacks since their reinstatement over 35 years ago clearly demonstrates this. Hopefully, legislators will see the value in maintaining corporate determination of their own capital allocation while banning practices like open market activities that, in many cases, are clearly against the interest of every stakeholder outside of the executive suite.