This post first appeared at The Felder Report PREMIUM.

The theme this week was again, “this time is different.” Sir John Templeton famously called these, “the four most dangerous words in investing,” but that hasn’t stopped many pundits from pointing out the obvious ways in which this time is truly different from the past. And I don’t disagree with them. In fact, we have seen this plenty of times before. During the late-1920’s stocks rose to valuations that were unprecedented at the time. They did so again in the late-1990’s.

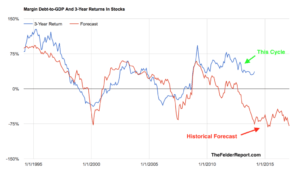

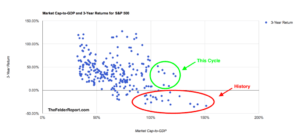

And it’s true once again that things are now very different than what we have witnessed previously in the markets. The median stock in the S&P 500 has never been valued higher than it is today. Corporate profit margins over the past decade have soared and sustained at heights rarely if ever seen before. In the past, margin debt was a valuable way to assess risk in the stock market. This relationship has broken down in recent years. The Buffett Yardstick was also not just a good way to assess forward 10-year returns for stocks but also 3-year risk in the stock market, as well. During this cycle this relationship has also failed. Finally, the relationship between demographics and equity valuations has also broken down in recent years.

And it’s true once again that things are now very different than what we have witnessed previously in the markets. The median stock in the S&P 500 has never been valued higher than it is today. Corporate profit margins over the past decade have soared and sustained at heights rarely if ever seen before. In the past, margin debt was a valuable way to assess risk in the stock market. This relationship has broken down in recent years. The Buffett Yardstick was also not just a good way to assess forward 10-year returns for stocks but also 3-year risk in the stock market, as well. During this cycle this relationship has also failed. Finally, the relationship between demographics and equity valuations has also broken down in recent years.

We can speculate about any number of causes for these phenomena including global central bank coordination in attempting to create a wealth effect, the mania in price-insensitive strategies like passive investing or the abnormally high risk appetites of baby boomers during this cycle. Who knows the real reason? I suspect it’s some combination of them all.

But what those who claim “this time is different” are really saying has nothing to do with the present phenomena. What they are really saying is that things will continue to be different in these ways forever. Not only do the old methods not work right now, they propose, they will never work again. In other words, there has been some seismic shift that has vaulted us into a new era where the old methods and measures no longer apply

But what those who claim “this time is different” are really saying has nothing to do with the present phenomena. What they are really saying is that things will continue to be different in these ways forever. Not only do the old methods not work right now, they propose, they will never work again. In other words, there has been some seismic shift that has vaulted us into a new era where the old methods and measures no longer apply

This is precisely the part of this popular sentence that Templeton was warning about. He wasn’t warning about unprecedented occurrences that are obvious to all. He was warning about extrapolating them indefinitely into the future. In essence, he was warning investors about the dangers of recency bias.

It’s not difficult to argue this time is different. It’s much more difficult to argue the next time will also be different and in the very same way this time is different. And the next time and the next time, too. Investors who have spent any time at all in the markets longer than just the current cycle understand the wisdom in Herclitis: “The only constant is change.” There is no such thing as a, “permanently high plateau.”

The change I believe is coming is a reversion in which these historical relationships begin to reassert themselves and even reverse the distortions of recent years. This is the sort of change history teaches us is inevitable. So while “the only constant is change,” that change itself is always constant. Hence, the famous warning from Sir John.

In tracking the progress of such a reversion, we will want to watch sentiment. Certainly, the recent inflows into passive equity ETFs look like a classic euphoric blowoff.

Buying panic in equity ETFs https://t.co/qRa8KOgR3N pic.twitter.com/FmfajOugwL

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) April 6, 2017

More and more pundits are coming to the conclusion that the popularity of passive investing is indeed a mania, a theme I’ve written about for the past couple of years.

'We are witnessing a mania in low transaction costs, average returns and on-demand liquidity.' https://t.co/rnJJEtgFpn

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) April 3, 2017

Furthermore, this mania has manifest in ways that are greater and more pervasive than anything we have ever seen before. While equity valuations are totally unprecedented so is corporate leverage, which now is reaching heights normally only seen during recession. The combination of the two is truly breathtaking and it’s finally drawing notice in the mainstream media.

Not a Dot-Com Bubble, not 2007, but a Nasty Mix of Both https://t.co/J2AALO4XHZ pic.twitter.com/ojgkNEeC77

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) April 7, 2017

At the same time, people are starting to realize that persistent stagnation is still exerting its economic pull.

On April 7, the #GDPNow model forecast for real GDP growth in Q1 2017 is 0.6% https://t.co/aXy389gnsB pic.twitter.com/YaDFUBoWmb

— Atlanta Fed (@AtlantaFed) April 7, 2017

In fact, it is very likely that stagnation could be the best case scenario going forward.

Stalling Engines: The Outlook for U.S. Economic Growth

– Hussman Market Comment 04/03/17 https://t.co/ZnpLWHAbv0 pic.twitter.com/UBN0jPzXRQ— HussmanFunds (@HussmanFunds) April 3, 2017

Retail is already very bad and getting worse.

Retail bankruptcies on pace to surpass 2009 peak https://t.co/mu2BYPUfs3 pic.twitter.com/Cuoc2aPQFQ

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) April 4, 2017

Auto sales are now following suit…

'What's bad for General Motors is bad for the stock market.' https://t.co/OUMVvxREm2 pic.twitter.com/H20SMjdLCN

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) April 4, 2017

…as is credit.

Fading Trump rally threatened by rare contraction of US credit https://t.co/RVS34fKljv pic.twitter.com/LpuK8jWtqV

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) March 27, 2017

Amid these growing signs of economic weakness, the Fed has decided to take away the punch bowl. Because the economy is now so highly levered they also have more power to do so than ever before.

"Even a modest tightening cycle can have a substantial restraining effect on both inflation and economic activity." https://t.co/kk8qnQ24vi

— Pedro da Costa (@pdacosta) April 4, 2017

This is where hope, as represented by the recent rally in risk assets, meets with reality and it’s not going to be pretty.

The gap between soft and hard data (hope and reality) has never been greater https://t.co/nHLN9dIinN pic.twitter.com/nGwM9oD9vB

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) April 3, 2017

It’s also where the smart money profits at dumb money’s expense.

The smart money is record ‘short’ in stocks, and the dumb money is record ‘long’ https://t.co/7zCXr3rVSU ht @WhatILearnedTW pic.twitter.com/PWWDcBBNl3

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) April 6, 2017

The smartest of the smart money knows the score.

The Fed is "going to ruin us all," veteran investor Jim Rogers says https://t.co/otlPc1JS85 pic.twitter.com/3ZvtjXb20x

— Bloomberg TV (@BloombergTV) March 28, 2017

I know it’s been unusually quiet lately.

The Quietest Quarter for the Dow Jones Industrial Average in 51 Years https://t.co/yGYKmFwxUq pic.twitter.com/fyfFbA0sm6

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) April 3, 2017

But as I have mentioned in recent market comments and in this week’s chart book, the parallels to 1987 are many. Stay vigilant.

'History may not repeat itself but it does rhyme.' https://t.co/joHcjPP0dL pic.twitter.com/PGINixZt7j

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) April 4, 2017

Being an investment adviser has probably never been more difficult than it is today. Not because of all of the competition coming into the industry or the pressure on fees. But simply because determining the most prudent course of action and then trying to get others to follow it in the midst of the most pervasive financial bubble in history is just incredibly difficult if not impossible in many cases.

How do you exercise “prudence and reasonable care” in managing another’s financial assets at a time when they have never been more overvalued? Do you just go to cash? How then do you justify an advisory fee? Or do you just raise more cash than normal and try to diversify away from the most obscenely overvalued segments of the financial markets? Do you try to implement some sort of hedge against massive losses in risk assets that seem as probable as ever over the next several years?

These are all good questions but the most difficult to answer is this: How do you get the average investor to go along with such price-sensitive prudence amid the greatest mania in price-insensitive strategies we have ever seen? Even if you determine what you believe is the right course of action it is a massive task to try to convince most investors of its merits when the recent profits from a passive approach make it seem like a no brainer.

For this reason, prudence most likely leads to loss of assets under management. Just look at Jeremy Grantham & Co. A third of the firm’s assets have walked out the door simply because they have been too conservative in the eyes of their clients. This $40 billion has no doubt migrated from the iconically price-sensitive Grantham to iconically price-insensitive index funds. If it can happen to Grantham it can happen to anyone.

Obviously, most advisers aren’t willing to tolerate this sort of hit to their top line so what do they do? They begin to offer the sort of price-insensitive strategies their clients want. John Maynard Keynes noted a century ago, “A sound banker, alas! is not one who foresees danger and avoids it, but one who, when he is ruined, is ruined in a conventional and orthodox way along with his fellows, so that no one can really blame him.”

It is far easier for an adviser to buy into the bubble by going passive and keeping assets in house – even it means eventual ruin for his clients and possibly himself – than it is to actually do the right thing from both an investment and an ethical perspective. But this doesn’t make it right. The right thing to do is almost always the hardest thing to do. For advisers this means taking the path of prudence even it means a not insignificant dent in his income.

For the few still fighting the good fight, my hat is off to you.