Back in May I wrote a post arguing that the record-high levels of margin debt should make investors more cautious. Basically, there is compelling evidence to suggest that margin debt is a very good indicator of long-term fear and greed in the stock market.

When margin debt is relatively high it signals that greed is predominantly driving stock prices. Conversely, when margin debt is relatively low it indicates that fear is the predominant factor. If an investor believes it’s wise to ‘be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful,’ as Warren Buffett suggests, then it’s probably going to be hard to find a better indicator for long-term investors looking to do so.

This also makes perfect sense from an economic viewpoint. Relatively high levels of margin debt suggest there is little potential demand left for equities and plenty of potential supply to pressure prices lower. Conversely, relatively low levels of margin debt suggest there is little potential supply and plenty of potential demand to pressure prices higher. And, in fact, this is exactly how margin debt has worked its magic on stock prices over the past 20 years.

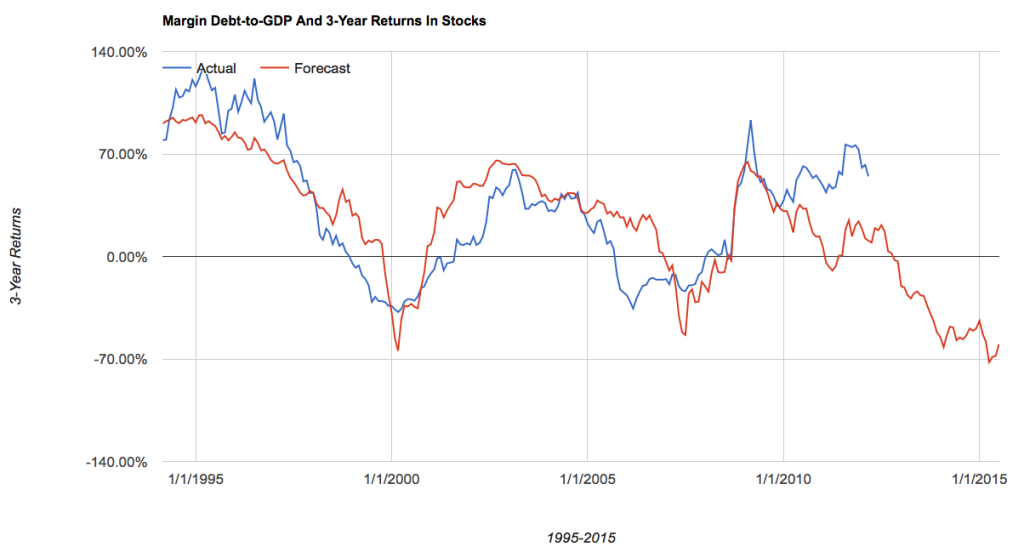

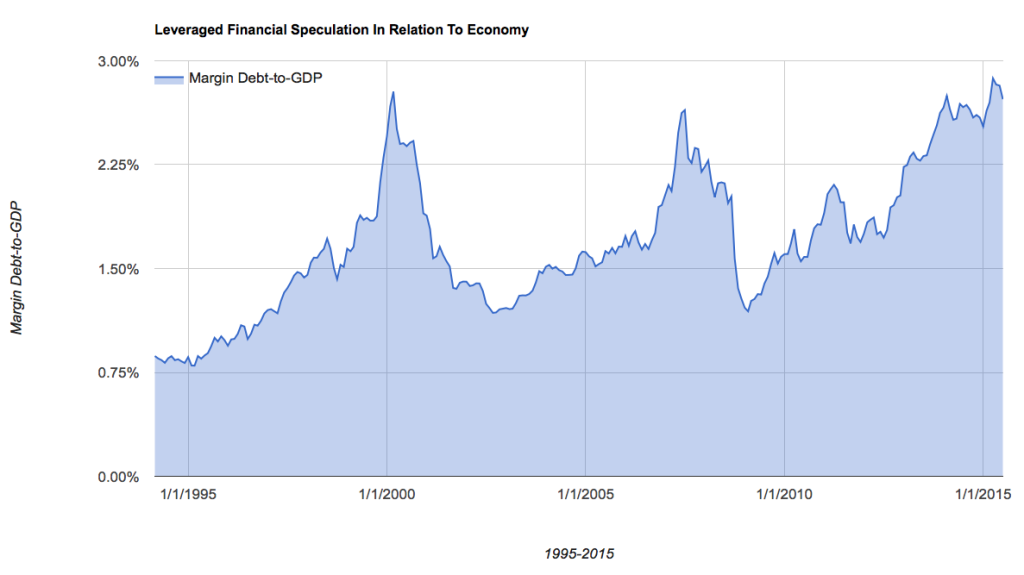

One of the most valuable ways I have found to view margin debt levels is in relation to overall economic activity. The chart below shows that when margin debt has approached 3% of GDP in the past it’s usually been a good signal that greed has gotten out of hand. Back in April this measure hit a new record.  The reason I find this measure so valuable is that it is highly negatively correlated to 3-year returns in the stock market. When margin debt relative to the economy has gotten very high, 3-year returns have been very poor and vice versa. Right now this measure suggests the coming 3 years in the stock market could be very similar to the last two bear markets we witnessed in 2001-2002 and 2007-2008 after margin debt reached similar levels in relation to the economy.

The reason I find this measure so valuable is that it is highly negatively correlated to 3-year returns in the stock market. When margin debt relative to the economy has gotten very high, 3-year returns have been very poor and vice versa. Right now this measure suggests the coming 3 years in the stock market could be very similar to the last two bear markets we witnessed in 2001-2002 and 2007-2008 after margin debt reached similar levels in relation to the economy.

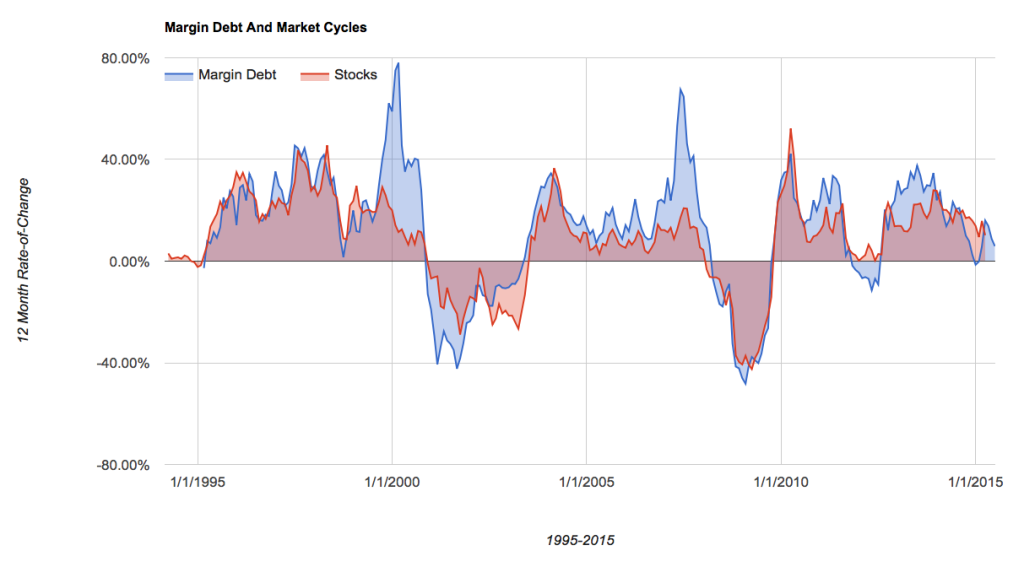

What’s more, in the past, when stocks’ 12-month rate-of-change has turned negative it’s usually triggered a significant reduction of margin debt. In other words, once the stock market starts declining over a year’s time record levels of margin debt, which functioned as demand to push prices higher in the past, start to become supply, which pushes prices lower going forward. This is how the last two bear markets began.

Now the stock market only needs to rise by about 3/4 of a percent today in order to maintain a positive 12-month rate-of-change. On the other hand, the longer the current correction in stocks continues the likelier we are to see it evolve into a longer-term bear market, as the massive amount of margin debt stops working in the favor of all of these “greedy” speculators and begins to work against them and they start to become more “fearful.”

And if the past couple of full market cycles are any guide, the potential supply coming to market in this scenario could make the next bear market another very painful one, at least for those who ignore the crystal clear message of margin debt relative to the economy.