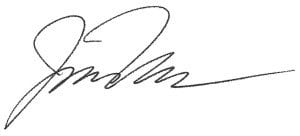

It was just over two years ago I wrote about The Fantastic Four That Make FANG Look Tame. McDonald’s, Caterpillar, Boeing and 3M, known in these pages as MCBM, had seen their stock prices, as a group, soar over 120% during the prior two years, more than doubling the performance of the S&P 500 and blowing away any other group you might want to compare them to including the vaunted FANG stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google).

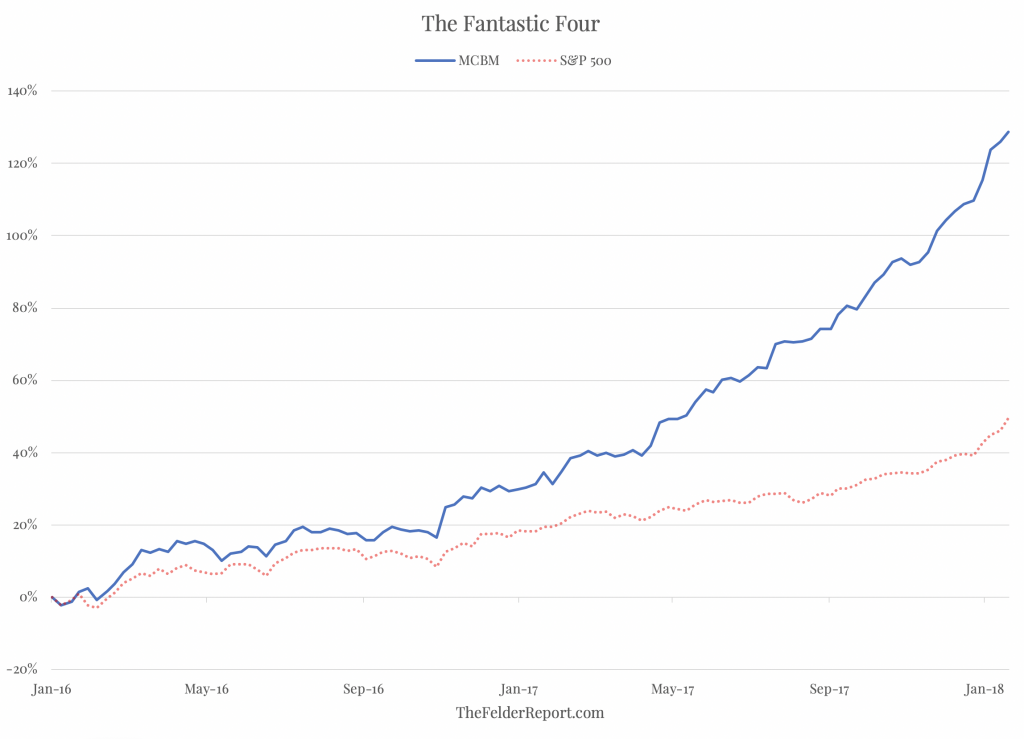

At the time I would astounded by the outperformance of these old, blue chip stocks and was curious to understand what was driving it so I dug a bit into their valuations. What I found was that it was entirely due to an expansion of their valuations to heights never before seen. What made this even more impressive was the fact that this came in response to record low revenue growth. Somehow, investors saw fit to reward these companies by paying unprecedented prices for their equity relative to their sales even as their long-term sales growth was turning negative for the first time ever.

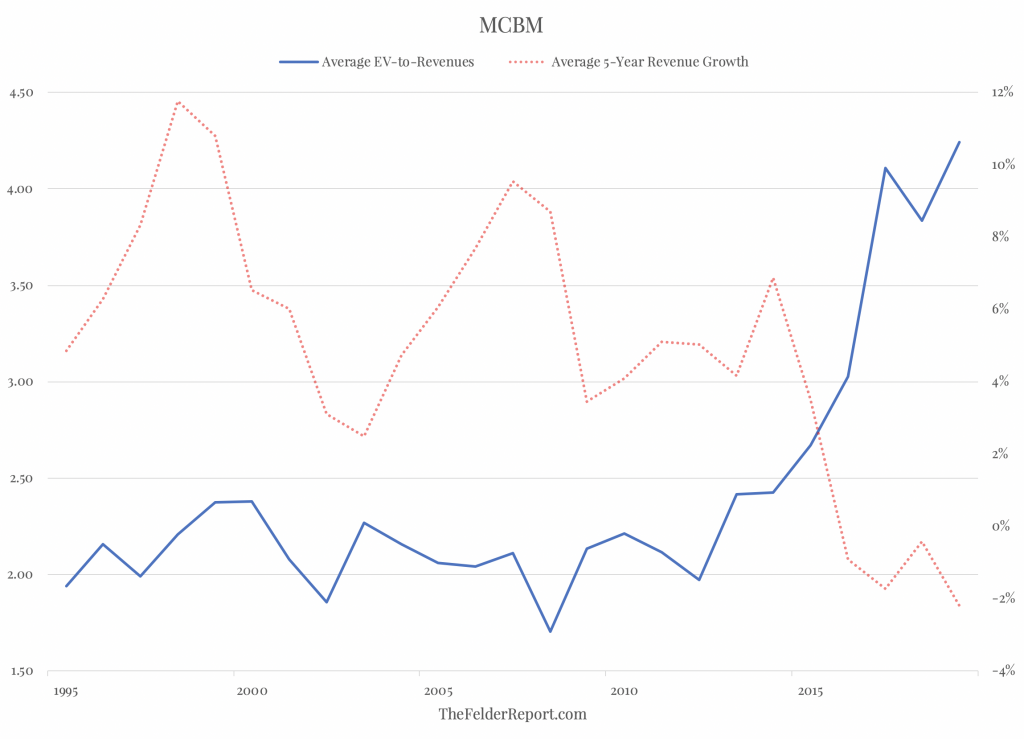

The explanation for this enigmatic episode was not too difficult to discover, however, once you took a look at their balance sheets. Over the past several years MCBM has issued a record amount of debt to buy back stock in massive quantities. This resulted in both the debt and the equity sides of their enterprise value calculation (market capitalization plus net debt) exploding even as sales growth imploded.

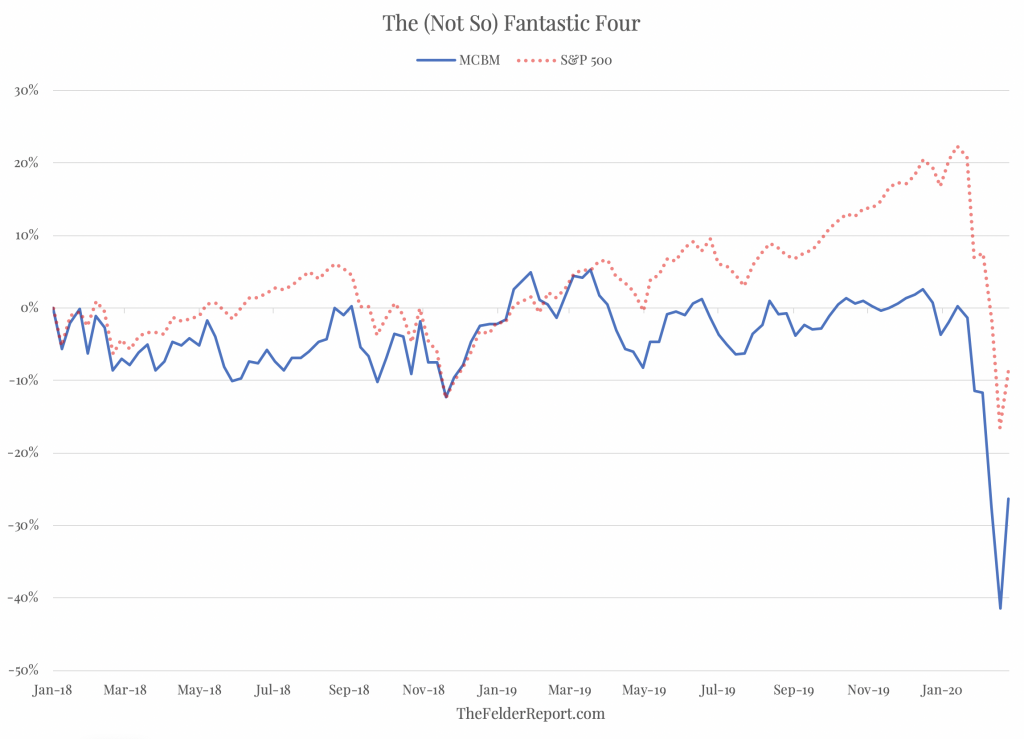

The success of this financial engineering, however, is already coming into question. Since that earlier post on the topic, the MCBM stocks have dramatically underperformed the market.

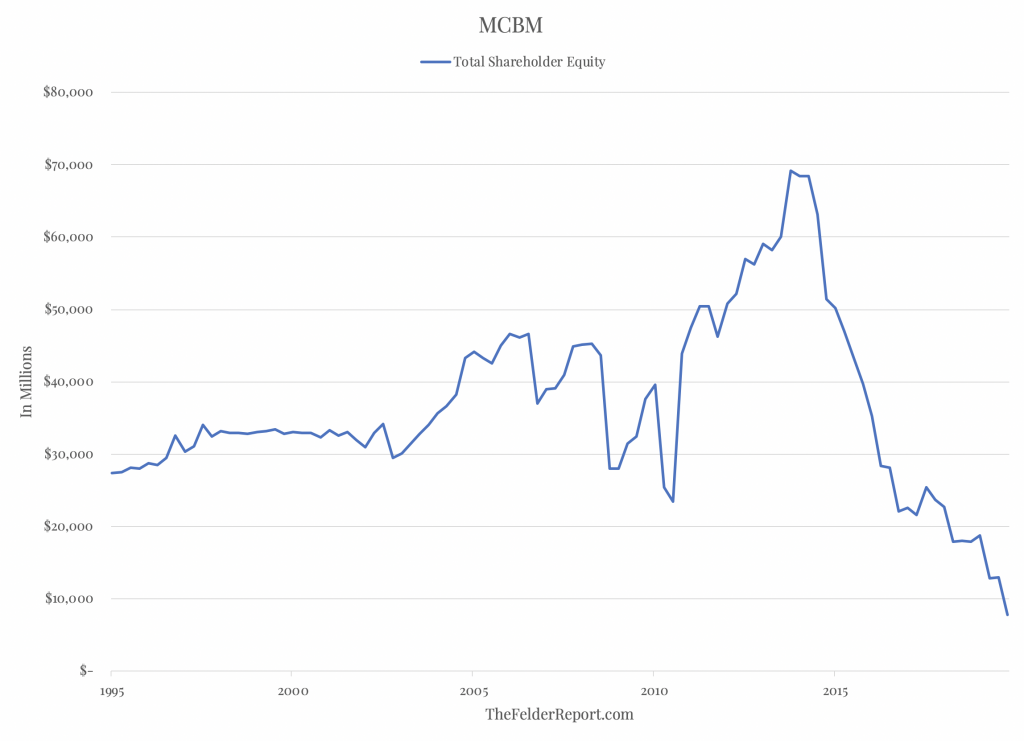

And all of that new debt now on their balance sheets, which is not offset by any new assets to speak of, could soon live up to the term “liability” during the nascent, coronavirus-catalyzed downturn. The best visualization of the predicament is the chart of the total net asset value of the four companies below. It has fallen 90% from $70 billion just a few years ago to about $7 billion today.

And while this precarious financial position should not inspire much confidence in shareholders, the fact that these stocks are still more expensive than they were at prior major market peaks (let alone troughs) should be even more worrisome. For this reason, the potential for further downside, even after losing more than a third of their values already, is significant.

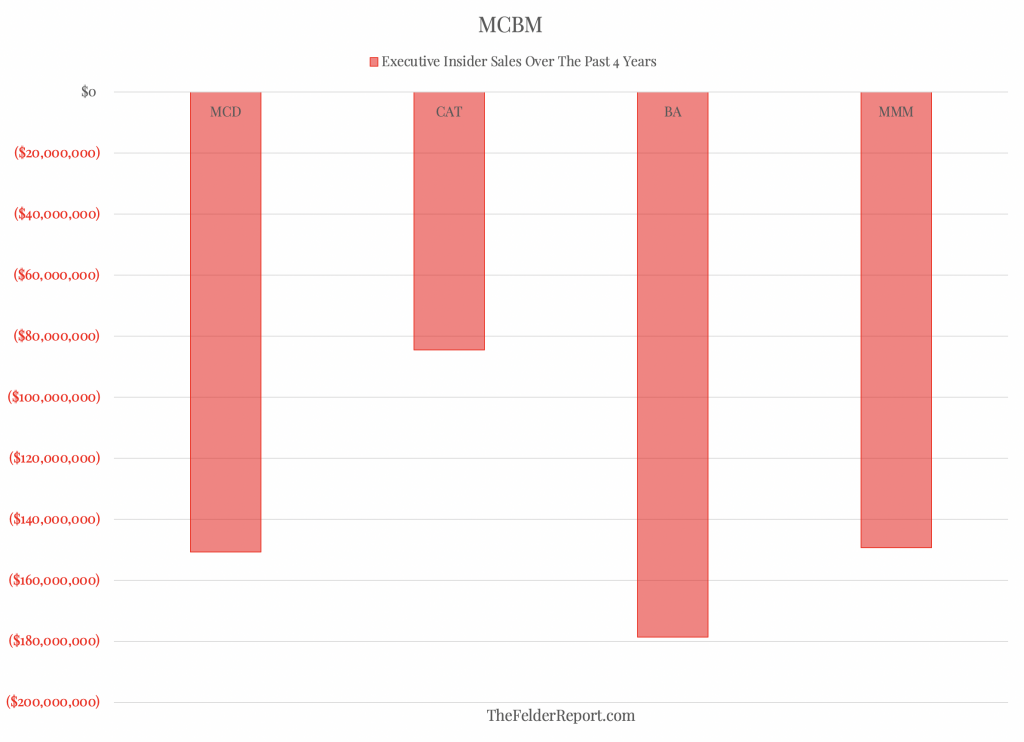

So the question becomes, ‘Why did these companies sacrifice long-term financial health for short-term stock prices gains?’ The answer lies in a little-noticed line on their cash flow statements labeled, “stock based compensation.” On average, these companies each spent $200 million per year on issuance of options to top management. Those very same managers were the ones who decided it was a good idea to leverage the balance sheet to buy back stock. At the very same time, they also decided it wasn’t a good time to be a holder of those shares and so they sold, collectively, over half a billion dollars worth of their own shares in the open market. As I wrote about year ago, “If This Isn’t Stock Manipulation, I Don’t Know What Is.”

In conclusion, it looks pretty clear to me that the decision to leverage up the balance sheet to buy back stock had nothing to do with returning capital to shareholders or any other such nonsense. It was done entirely to boost earnings per share ensuring executive bonuses that would become even more valuable if the shares they were paid in were inflated through persistent manipulation by the company itself. In other words, management got rich in the short run at the expense of the long-term health of the companies they ran. I guess we’ll see how well that continues to workout for their remaining shareholders.