This post is an excerpt of a recent market comment that first appeared at The Felder Report Premium.

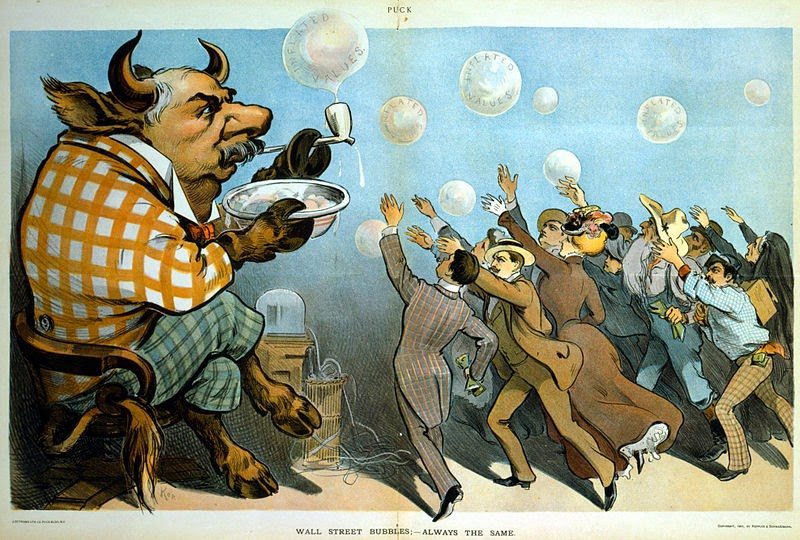

With the failure of the WeCompany (formerly WeWork) IPO, many have become critical of the now obvious follies in the private markets. However, they clearly fail to appreciate what this means for the public markets. “Asked whether they often make a gut decision to invest in a fledgling company rather than relying on analysis, 44% of venture-fund executives said yes. Which financial metrics do they use to analyze investments? ‘None,’ admitted 9% of respondents,” wrote Jason Zweig recently for The Wall Street Journal, implying the lack of discipline is to be blamed for the bubble in venture capital.

'Normal markets consist of pessimists, neutral people and optimists, who can take either side of a trade. But that’s not the case in a private market, where it’s difficult to sell and pessimists can’t easily express a view.' https://t.co/EoqhqVK8Zw

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) September 20, 2019

However, this begs the question: how many investors in the public market today are failing to use financial metrics to analyze investments? Certainly, with funds in passive products recently surpassing funds in actively managed ones it would appear that the answer would be over 50% of investors in public funds. So if 9% of venture capital investors are able to create a bubble in that market by buying without any regard for value, what are the 50% in the public funds capable of?

Funds that track broad U.S. equity indexes hit $4.27 trillion in assets as of Aug. 31, giving them more money than stock-picking rivals for the first-ever monthly reporting period. https://t.co/2UlLzQRRbU pic.twitter.com/PYID9LG01Q

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) September 26, 2019

With the shift in perception towards these private market behemoths, epitomized by the WeCompany fiasco, it’s inevitable we will see a very similar shift in the public market. Investors will soon come to realize once again that equities, private or public, are not the easy path to riches they have seemed to be over the past decade; they are worth nothing more than the discounted value of their future cash flows (and not discounted at today’s “risk-free” rates but at a more historically appropriate rate). And that true value is far lower than current prices.