The following is an excerpt of a recent market comment that first appeared at The Felder Report Premium.

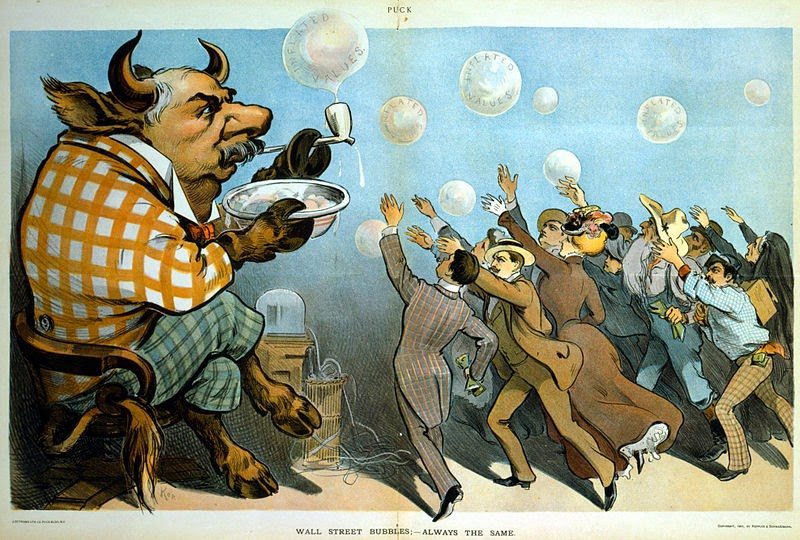

What is the opposite of a margin of safety? That is a question this market has had me asking myself for some time now. A margin of safety is a discount to intrinsic value that provides a safety net in the result of an error in analysis or unforeseen negative developments. The opposite of a margin of safety then is a premium to intrinsic value than can vanish even if your analysis is correct or things go unexpectedly in your favor. There are times when a security reaches a valuation such that even if everything goes right you’re unlikely to profit. The price has already discounted a perfect outcome. This “priced for perfection” scenario is the opposite of a margin of safety and this is currently where the stock market finds itself today.

So what exactly is this perfection that is currently built into stock market valuations? First, equity valuations have risen in recent years to their record heights at present as a result of investors making a classic mistake. Whether consciously or unconsciously, they have essentially lowered the discount rate in their valuation models without also lowering the assumed growth rate of earnings. As Cliff Asness demonstrated years ago in his paper “Fight The Fed Model,” this is clearly irrational behavior. Because interest rates and earnings growth are so highly correlated one cannot be modified without the other in a discounted cash flow model. In other words, falling interest rates do no justify higher equity valuations. This doesn’t, however, stop investors from believing this very thing.

So what exactly is this perfection that is currently built into stock market valuations? First, equity valuations have risen in recent years to their record heights at present as a result of investors making a classic mistake. Whether consciously or unconsciously, they have essentially lowered the discount rate in their valuation models without also lowering the assumed growth rate of earnings. As Cliff Asness demonstrated years ago in his paper “Fight The Fed Model,” this is clearly irrational behavior. Because interest rates and earnings growth are so highly correlated one cannot be modified without the other in a discounted cash flow model. In other words, falling interest rates do no justify higher equity valuations. This doesn’t, however, stop investors from believing this very thing.

Furthermore, for this decision to pay higher prices as a result of lower interest rates to avoid a very painful outcome it requires that interest rates remain low indefinitely and that investors continue to make this error in judgement. In essence then it is a bet on interest rates and a “greater fool” trade in one. This is the perfect scenario embedded in the stock market today and it’s already discounted, meaning that even if it comes to pass investors stand to benefit very little if at all. However, should either fail to materialize the downside to equity valuations is significant. But this is not all that is required for today’s equity investor to come out unscathed.

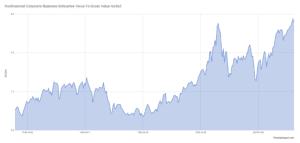

Price-insensitive buying on the part of passive investors, central banks and corporations themselves have been the primary demand drivers of equities in recent years. For equity valuations to avoid reverting closer to a historical average these will be required to at least maintain their current pace of buying. Most importantly, record corporate stock buyback activity will be required to continue to make up for the demographic headwind to equity valuations.

The question of, “Who will baby boomers have to sell to?” is about more than just real estate. It’s also about equities. The Fed has estimated that over the coming years demographic trends could mean the stock market reverts to a price-to-earnings ratio of 8 versus 24 today. Without record stock buyback activity or radical central bank intervention this outcome becomes a near certainty. Thus there is another perfect scenario embedded in today’s equity valuations, that the current price-insensitive demand will continue indefinitely.

Finally, there is a third embedded assumption in today’s stock prices that may present the most poignant risk at present. This is the assumption that record corporate profit margins, enabled by record low labor share, will also be maintained indefinitely. What most investors don’t understand today is that the price-to-earnings ratios they use to value any stock in the market at all are entirely reliant on sustaining margins at levels that have been historically unsustainable. Again, this assumption has already been discounted by the market.

Think of it this way: As mentioned above, the current price-to-earnings ratio of the S&P 500 is roughly 24 versus a historical average of about 15. However, should profit margins revert to a more normal historical level that valuation could soar to 35 or 50 times earnings as the denominator falls. In this scenario there is not only the potential risk of a reversion in valuations but also a reversion in profit margins at the same time, a scenario that would be doubly painful for equity investors paying current prices. Thus the premium embedded into today’s stock market also assumes profit margins will avoid reverting to historical averages.

I have written that the single greatest mistake investors make is extrapolating recent history out indefinitely into the future. Today, they may be extrapolating more than ever before. It would be something if the current equity market was discounting just one of the current extremes mentioned above being perpetuated indefinitely. I believe there is a case to be made that it is discounting all of them. And if that’s true investors stand to profit very little from them actually coming to pass in the years ahead. At the same time, if any one of these fail to materialize the downside risk to equity prices, just like current valuations, may be unprecedented, as well.