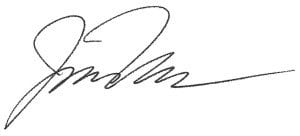

“A Long Time Ago In A Galaxy Far, Far Away… [there was a thing called inflation.]”

“Demographics are destiny.” This catchy saying has become very popular among the deflationistas in our midst. They posit that an aging population will inevitably make for slower growth and inflation in coming years hence today’s ultra-low interest rates are here to stay. Ultra-low interest rates have clearly inspired investors to reach for yield in corporate bonds and stocks so it is hard to see how the current status quo, if it does not change, could allow for a bursting of the everything bubble.

It’s May the 4th as I’m writing this. Star Wars day. And as I hear this “demographics are destiny” line in my head I am reminded of the climactic scene in Return of the Jedi when Emperor Palpatine tries to entice Luke Skywalker to the dark side: “It is unavoidable. It is your destiny. You, like your father, are now *mine*.” Like the emperor, the deflationistas want to convince us that this darkness is unavoidable. Like Luke Skywalker, I have trouble with this view.

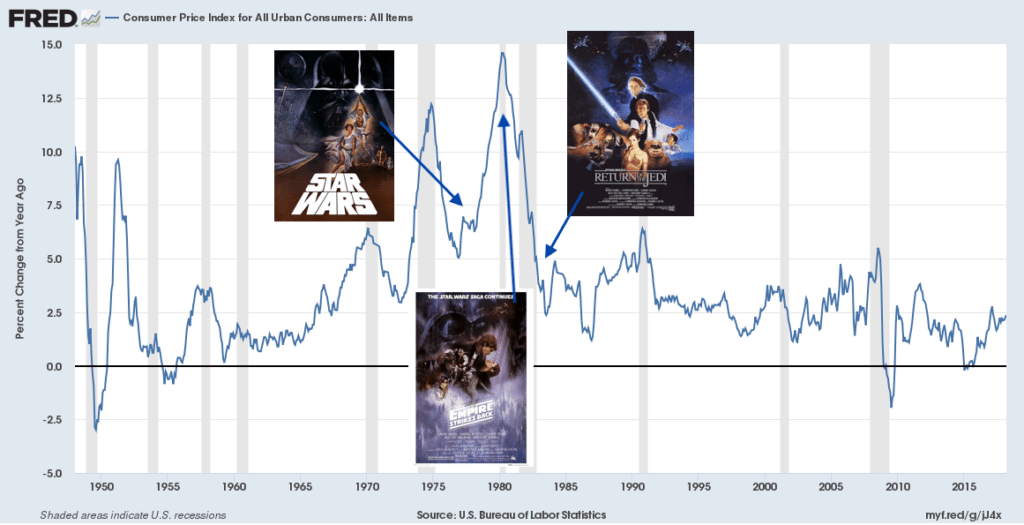

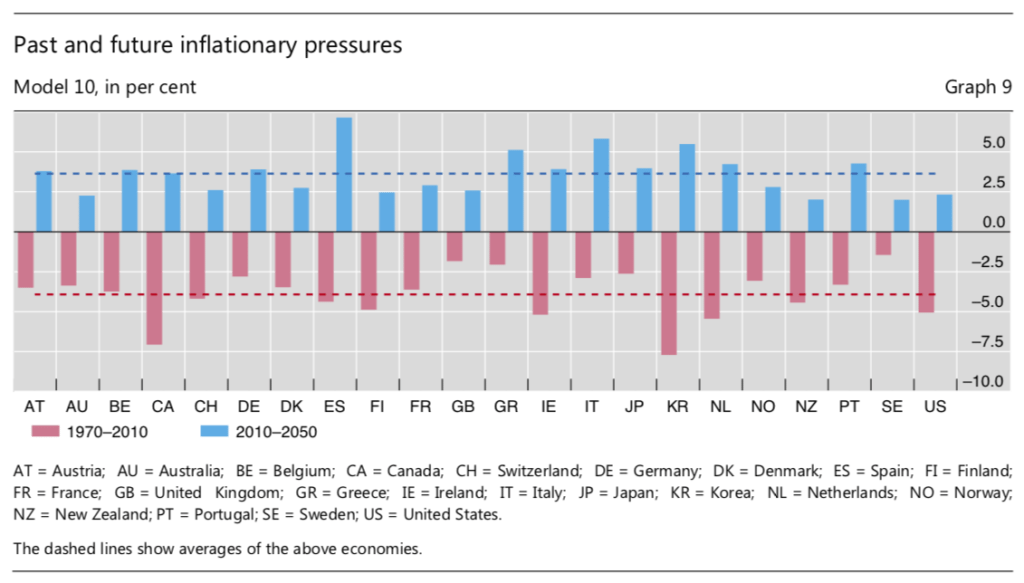

The trouble I have with it is that there is no evidence I have seen to support the idea that an aging population inevitably leads to deflation. In fact, the only evidence I have seen in regards to this idea directly contradicts it. Demographics are indeed destiny but the data suggest an aging population will make for rising inflation, rising interest rates and thus lower valuations for financial assets like stocks and bonds. I recently came across a BIS Working Paper that makes this first point pretty clear (Can Demography Affect Inflation and Monetary Policy?, hat tip, J. Brett Freeze):

According to our estimates, demography accounts for around one-third of the variation in inflation and for the bulk of the deceleration between the late 1970s and early 1990s. Furthermore, our estimates reveal a stable U-shaped pattern: a larger share of dependents (ie young and old) is correlated with higher inflation, and a larger share of working age cohorts is correlated with lower inflation.

In other words, the great disinflation of the last 40 years is largely just a product of an improvement in the age dependency ratio. Now that this ratio is reversing these trends should follow suit.

The paper doesn’t do much to explain why this relationship exists but it stands to reason that it is much more costly for an economy to care for dependents both young and old than it is to sustain a large working age population that largely provides for itself. Just look at the greatest drivers of inflation in recent years. College and healthcare costs have risen much faster than most others. Considering end of life costs are astronomical right now, it’s not hard to see how an aging population could make for higher inflation.

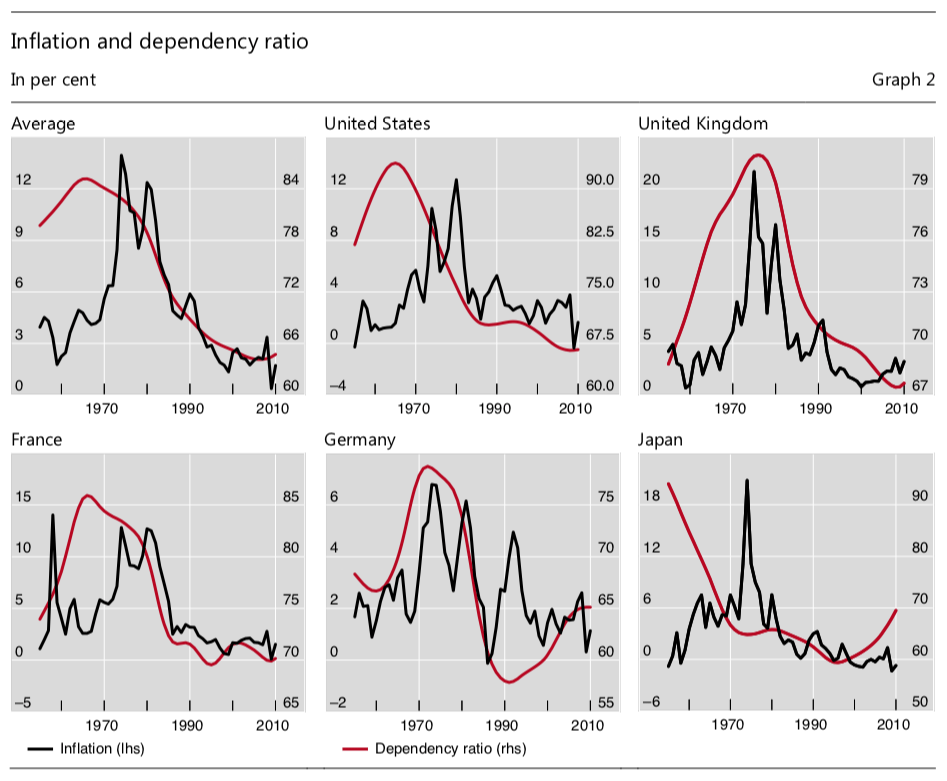

Interestingly, the disinflationary trend of the past 40 years, driven by the demographic tailwind, has provided an unprecedented tailwind to the prices of financial assets, especially equities. Obviously, lower inflation is going to make for lower interest rates and higher bond prices. But it’s also clear that, although it is not entirely rational, investors have been inspired by low inflation to put a higher value on equities than they probably should. A paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco outlined this phenomenon over a decade ago (Inflation-Induces Valuation Errors in the Stock Market):

Studies show that the Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500 stock index tends to be undervalued during periods of high expected inflation (such as the late 1970s and early 1980s) and overvalued during periods of low expected inflation (such as the late 1990s and early 2000s). This result implies that the long bull market that began in 1982 can be partially attributed to the stock market’s shift from a state of undervaluation to one of overvaluation. Going forward, the return on stocks could be influenced by a shift in the opposite direction.

Certainly, the conclusion was a bit premature. Inflation has continued to trend down since its October, 2004 publication date. However, there are clear signs cyclical inflation is now picking up as I have chronicled in recent market comments. And on a secular level it also looks like the winds are now changing. This disinflationary demographic backdrop for nearly every country on the planet is now shifting to an inflationary one. Thus, based upon investor behavior toward inflation alone, we should expect the 40-year trend from undervaluation of equities to overvaluation of equities to reverse course and even retrace completely.

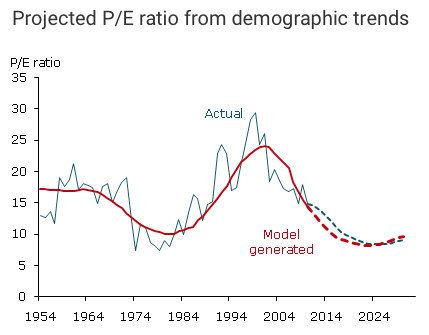

Here again, demographics provide additional supporting evidence for this thesis. Another product of shifting demographics from primarily a working-age population to an old-age population is lower equity valuations. Here again, we have another paper from the San Francisco Fed to support this thesis (Boomer Retirement: Headwinds for U.S. Equity Markets?):

In our view, the saving and investment behavior of the old-age cohort is more relevant for asset prices than the behavior of young adults. Equity accumulation by young adults is low. To the extent they save, it is primarily for housing rather than for investment in the stock market. In contrast, individuals age 60–69 may shift their portfolios as their financial needs and attitudes toward risk change.

In other words, the baby boomers have a ton of equity to sell in coming years and there is no set of buyers capable of absorbing this supply. For this reason alone, equity valuations should come down in the future. In fact, the San Francisco Fed believes a multiple of earnings of just eight times could be likely at some point over the next several years. This compares to the current multiple of over twenty. If this prophecy comes true the next bear market will be a doozy.

Taken together, these three pieces of evidence all work in concert to suggest aging populations around the world are very likely to kindle rising secular inflationary trends which will result in the reappraisal of the value of financial assets, both stocks and bonds, migrate from overvaluation to undervaluation in the future. The secular increase in the supply of these assets coming to the markets in the context of waning demand as a result of demographic trends only reinforces these .

Higher inflation, higher interest rates and falling valuations for financial assets represent the real destiny, determined by demographics, of our economy and financial markets over the next several decades. And it’s hard to imagine a greater secular tailwind for the relative prices of real assets, most notably that of gold.

This Billionaire Has Put Half His Net Worth Into Gold https://t.co/jsCJVIKZgq pic.twitter.com/PHh592lLPT

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) May 1, 2018

We are already at the point at which the risk-free rate of return is far more appealing than that offered by risk assets.

The one-year US Treasury note yield rose to 2.06% during March and above the S&P 500 dividend yield for the first time since June 2008. https://t.co/9N7gucnnLd pic.twitter.com/p4oANiIRCq

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) May 4, 2018

Interest rates are rising because the inflationary pressures are becoming increasingly obvious.

Lincoln Electric: ‘We’re in a very rapidly increasing inflationary environment.’ https://t.co/ypwfrZ3pZz

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) May 2, 2018

And it’s becoming obvious in almost every sector of Corporate America.

Pepsi, Hershey, UPS and Caterpillar are just a few of the companies reporting growing pressure on margins from the rising costs of a range of raw materials, from fuel to freight costs to food and even wages. https://t.co/f4k77ICDpB

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) April 27, 2018

It’s only the hope that inflation is transitory and growth is rekindled that is propping up stocks at the moment but reality is just the opposite. Inflation is the new secular trend and it’s the recent pop in growth, as weak as it is, that is transitory.

Alan Greenspan: ‘We’re moving towards stagflation. It feels good right now but it’s a false dawn.’ https://t.co/SOvX42ptdj

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) May 3, 2018

Investors are only beginning to pick up on these trends and, more importantly, their implications for asset prices. As they realize that rising inflation and faltering growth are more than just a passing phase, the recent volatility in equities will be magnified.

If rising interest rates are being driven by inflationary pressures, suddenly the assumptions behind sky-high stock prices could fall into doubt. https://t.co/ByZmUVMB2z

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) April 26, 2018

And very similar to how the rapidly increasing supply of IPO’s helped to burst the dotcom bubble, the rapidly increasing supply of bonds, as a function of increased borrowing on the part of the government along with reduced buying on the part of the Fed, could quickly overcome the demand for investment assets in total.

Net Treasury borrowing totaled $488 billion from January through March, a record for that period and about $47 billion more than it had previously estimated. https://t.co/uIQ9tvs12a pic.twitter.com/DO8BzgBqzH

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) May 1, 2018

It also doesn’t help matters much that foreigners are seemingly losing their appetites for treasury securities.

Growing Concern: Foreign Investors Lose Some Hunger for U.S. Debt https://t.co/F4IFUpMLSB pic.twitter.com/h6MmLhKcwZ

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) April 30, 2018

The rapidly deteriorating supply/demand equation for our debt is really what sets us apart from the rest of the world. We are expected to be the only major nation on the planet to see our debt ratio increase over the next five years. This begs the question, “who is going to buy all of these bonds?”

#Debt ratios are projected to decline in all advanced economies, but one. https://t.co/2IDPWhZZeh #FiscalMonitor pic.twitter.com/6JMDEm0CND

— IMF (@IMFNews) April 18, 2018

Not the Fed. Rising cyclical and secular inflationary pressures are already forcing the Fed to unwind its “unprecedented ultraexpansionary monetary policy.”

Stan Druckenmiller: 'I shudder to think of the malinvestment that has occurred over the past six years as a result of unprecedented ultraexpansionary monetary policy.' https://t.co/sIopJUYnxH ht @NuitSeraCalme

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) May 3, 2018

The massive malinvestment in recent years that Stan refers to has mainly been focused in the corporate bond market and that is exactly where the greatest pain will be felt during the next downturn.

Corporate debt and equities will face the biggest pain when the next downturn comes because they have been the ones gorging the most on the ultra cheap interest rates during the past decade. https://t.co/Q7AvROGRqx ht @lisaabramowicz1

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) May 2, 2018

Leverage is off the chart.

‘Leverage in the U.S. is grotesque for this stage of the cycle. At the moment you’ve got peak leverage at peak prices. It’s not like you have to dig deep to find a problem.’ https://t.co/x5bAu5U0eZ ht @lisaabramowicz1 pic.twitter.com/UWUo1WNyDk

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) April 26, 2018

At the same time liquidity has never been poorer. The two combined are a recipe for a rout like we have never seen before.

‘Banks have moved from being warehouses of risk to being intermediaries. Markets are riskier now as a result.’ https://t.co/h2eqoakYKB pic.twitter.com/q6NgvW3a5R

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) May 3, 2018

If it were just corporate bonds that were the problem it would be enough to cause some serious pain in the portfolios of most investors. However, if the “end of the great debt super cycle,” to steal a line from Ray Dalio, is brought on by a new inflationary impulse it has implications for all financial assets.

'Bonds and equities falling at the same time is the portfolio wrecker.' https://t.co/IX3b1fj2TW pic.twitter.com/fwwHIEAQVX

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) May 1, 2018

The return of inflation means this “portfolio wrecker” of stocks and bonds falling in concert is exactly what investors should expect not just for the near term but over the coming decade and beyond.

'The rise in bond yields and concurrent shakiness in equity markets may emanate from a subtle but important shift in risk sentiment on inflation.' https://t.co/cSIDPhDOOY pic.twitter.com/6mAYbvDXHM

— Jesse Felder (@jessefelder) May 1, 2018

This won’t happen in a straight line; no trend in the markets ever really does. But these are the larger long term dynamics we want to pay attention to and real assets, most importantly precious metals, are likely to prove the only profitable way to navigate such an environment. To steal another line from Ray Dalio, “if you don’t own gold, you don’t understand history.” Or perhaps I should just say, “may the force [gold] be with you [in your portfolio].”