The strength in the FANGs (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Google) is what’s holding up the stock market this year. This is no secret. Everyone’s been talking about our new version of the “Nifty 50,” which is today something more along the lines of the “Nifty 4.”

In actual fact, it could really be considered the “Nifty 1” as Amazon has seen its stock price more than double this year, adding over $170 billion in market cap. Now at over $300 billion, the stock is now the 7th largest component of the S&P 500, making up 1.4% of the index. Coincidentally, that index is up just about 1.4% for the year right now so in some respects you could argue this one stock is responsible for essentially all of the gains in the index (I know this isn’t mathematically exactly accurate but the general point remains).

It seems the bullishness surrounding Amazon’s rise this year is due to the fact that it continues to take more and more market share from the likes of Wal-Mart, Target and others. This is partly evidenced by the fact these latter companies have seen their own stocks hammered recently to one degree or another. Yes, it’s once again “clicks versus bricks” in the financial markets.

To justify it’s current valuation, investors have talked about Amazon’s ability to one day, “turn on the profits.” Right now the company is simply focused on taking market share and during this process they don’t care about making any profit at all, as the story goes. But someday, this will change, investors say.

However, one thing Amazon investors may currently be overlooking is that the retail business, even for the best companies in the world, is generally not that profitable. In fact, these companies that Amazon is taking share from all have one thing in common: very thin net profit margins.

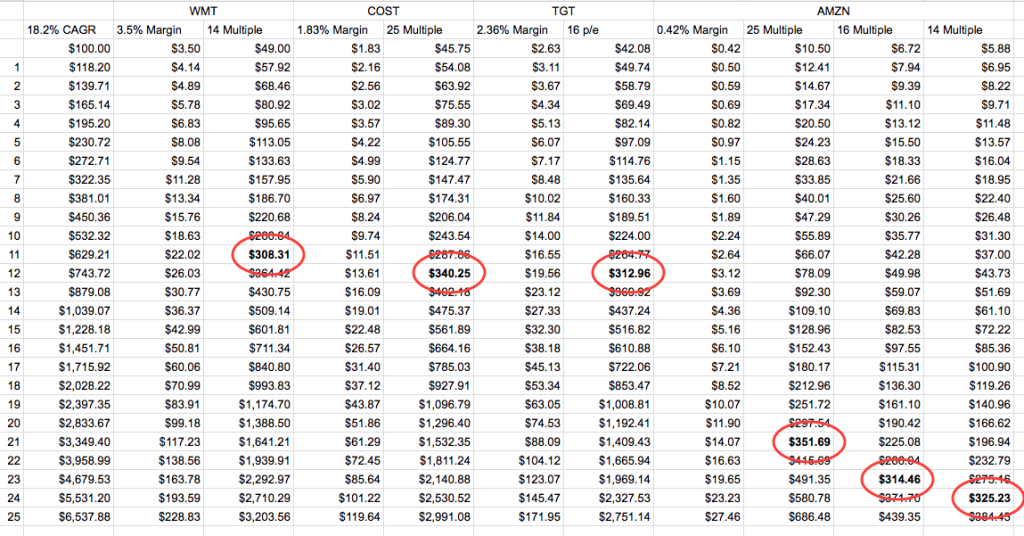

So I thought it might be interesting to run a little experiment to see when Amazon might actually grow into its current valuation assuming they do decide to turn on the profits at some point in the future. In doing so, I assumed Amazon would be able to continue to grow its revenues at 18% indefinitely (some might consider this a “heroic” assumption but let’s give Bezos the benefit of the doubt). I then applied the average profit margins of the company’s nearest “bricks and mortar” competitors along with those companies’ average profit multiples in the marketplace to come up with a valuation. Finally, I applied Amazon’s current average profit margin and these multiples just to see what it would look like if they decided to keep the profits spigot unchanged. The results can be seen in the spreadsheet below.

With a Wal-Mart-like profit margin (3.5%) and multiple (14 p/e) it would take Amazon 11 years to grow into its current $300 billion market cap, assuming it continues to grow revenues at 18% as it has over the prior four quarters. With a Costco-like margin (1.83%) and multiple (25) it would take 12 years as it would with Target-like metrics (2.36% and 16p/e). Finally, if the company decided to simply maintain its current average profit margin of 0.42% and investors still afforded it a multiple like its peers it would take over 20 years to grow into its current valuation.

Now, it needs to be said that an 18% growth rate for perpetuity means the company will be doing over $6 trillion in sales 25 years from now. For a little perspective, Wal-Mart is already the largest company in the world by sales at nearly half-a-trillion. Personally, I don’t really doubt Amazon can become the largest by sales but it may be unrealistic to assume they can generate more than ten times the sales of the current largest in the world.

What’s more, I think the pertinent question investors must ask is this: ‘Even if Amazon does decide to, “turn on the profits,” at some point in the future what is the likelihood they can sustainably generate a profit margin similar to their top competitors while maintaining their current sales growth and market share?’

Now, I love the company. And, as a nation of consumers, the country clearly loves it, too. Over the past few years, I’ve started ordering more and more from Amazon. In fact, while writing this post my wife asked me if I wanted to see the new dress she’s ordering from the site (it’s gonna look great on her ;-). I’m sure many other Amazon customers are doing the same so the story, in this respect, is probably true.

Still, our loyalty to Amazon runs only as far as they offer the best price. As soon as someone offers a better price, consistently and with the same ease of purchase, our business will shift to them and away from Amazon just as quick as it shifted to Amazon and from its, “bricks and mortar,” competitors in the first place. To me, this suggests Amazon’s ability to, “turn on the profits,” is almost perfectly inversely correlated to their ability to generate sales growth and take market share.

Ultimately, the reason retail margins for all of these companies are so low is that it really is a commodity-like business. They don’t sell anything proprietary to any significant degree that gives them the ability to charge a greater margin.

As Warren Buffett has famously said, “In a business selling a commodity-type product, it’s impossible to be a lot smarter than your dumbest competitor.” And I’m sure Amazon CEO, Jeff Bezos, know that Wal-Mart, Target and Costco all look at Amazon right now as their, “dumbest competitor,” willing to sell the same products at essentially no profit margin.

So again, we have to ask: ‘What is the likelihood that, should Amazon decide to, “turn on the profits,” a new, dumber competitor sees the opportunity to take share from Amazon by undercutting their raised prices?’ I’d say that it’s probably pretty high, especially considering what venture capitalists have been willing to fund over the past couple decades (see Jet.com as the latest example).

It seems to me that a 10-year time frame for Amazon to grow into its current valuation may be closer to a best-case scenario than anything because it assumes the company can both, “turn on the profits,” and maintain it’s current sales growth and market share gains. If it’s unable to accomplish both of these at the same time, investors in the stock may be left in lurch for quite a long time as it will only become harder to justify the valuation as the company continues to grow.

Finally, the fact that this investment thesis can be considered the driving force behind this year’s stock market gains should tell you much about current sentiment towards equities generally. In my view, it suggests there’s a whole lot of hope driving the stock market and not a whole lot of reality right now.

UPDATE: Yes, I set aside the whole AWS discussion for now. At about 10% of company revenues it’s not a huge part of the business and my personal opinion is that it’s also just another commodity-like product. Someone could easily come in and beat them at their own game in this line of business. The question is, ‘How dumb to Google and Microsoft feel?’ So even considering AWS, the growth and profit margin argument remains.