A week ago I put out a call to the bulls. I was looking for someone to demonstrate why stocks are likely to outperform the risk-free rate over a number of years (3,7 and 10 were the examples I gave). I’ve gotten a few responses since but they mostly feel like half-hearted attempts to explain why investors are still bullish rather than why they should be bullish.

Here’s a good example:

First off, I am in complete agreement with the observation (and your comments) that current valuations on US stocks are so high that rates of return over the next 7 to 10 years are likely to be very low to negative.

However, valuations have never been (as far as I can tell) a market timing mechanism. The broad history of the US stock market is that prices advance until a recession is imminent. Even after the declines in 1962 (Cuban Missile Crisis) and 1987 (Portfolio Insurance Debacle) the market went on to new highs before the next recession.

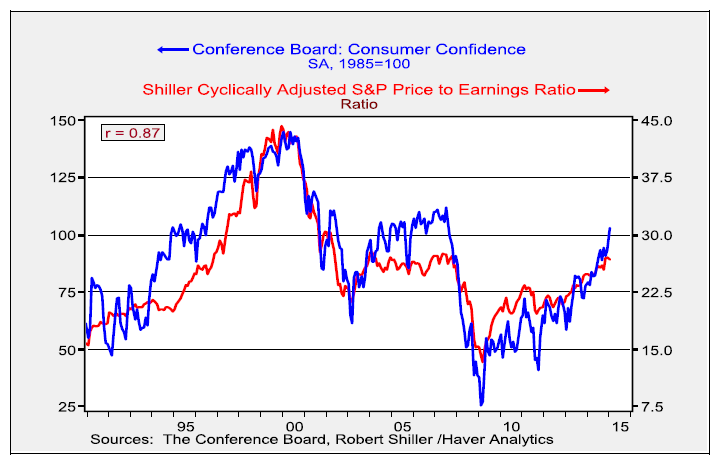

My supposition for why this occurs is encapsulated in the chart below. So long as the economy is expanding and as a result carrying consumer confidence higher, then investors (whether it is rational or not) will continue to pay higher valuations for equities.

Until there is a recession, investors are comfortable bidding stock prices higher.

Here’s another one:

Okay, I’m not REALLY a bull, but this is the best I could figure for a bull case for equities…

Executive Summary: Hyperinflationary Monetary Supernova (Fed buys all US Government debt and forgives it all).

Narrative:

- After a 20% dip in equities, the Fed panics and launches into QE4. Equities begin an aggressive rally.

- After some time, the Fed notices that equities have again stalled and the yield on the ten year note isn’t falling quickly enough for their tastes (perhaps spooked by all the money printing). So they buy Treasuries even more aggressively. Equities rally some more.

- But the bond market isn’t falling for it, and to keep Treasury rates low, the Fed ends up having to buy all of the Treasury market that is available to buy. Equities are going ballistic by now.

- Having defined inflation out of existence, and seeing no economic growth (even as interest rates continue to rise), the Fed decides that even more radical steps are necessary to protect the economy. After much internal deliberation, the Fed announces that it is forgiving all of the Treasury debt that it owns, and furthermore, it will continue to purchase new issuance from the Treasury department. The hyperinflationary monetary supernova sends equities soaring.

And another:

For the record I’m not a “bull” and don’t seek to make a bullish case for equities. I was intrigued by the challenge and allowed myself a few minutes to ponder.

At the risk of sounding philosophical, I am going to give you a philosophically-sounding answer. Think of an 8-yr-old boy asking his mom if Santa Clause is real. (He has some newfound doubts because he’s heard some naysayers at school talking.) Is Santa celebrated every year? Yes. What’s Santa’s track record? A perfect 8 for 8: a gift under the tree every year of the boy’s life.

It doesn’t matter what the boy should know, the truth; what matters is what he’s told to believe. As long as the common knowledge holds he can reasonably extrapolate forward. However, the moment he ceases to believe and tells his parents as much, his odds of receiving another gift from Santa drop dramatically. There doesn’t have to be a sound reason to support the bull case at this juncture. It is what it is until it isn’t.

These are all fascinating things to think about but none of them demonstrate why stocks are likely to outperform the risk-free rate over any number of years in the future. Still, I’ll tackle each one briefly here.

First, it’s true that bear markets usually coincide with recessions so it may be true that we are unlikely to see stocks decline meaningfully while the economy remains fairly strong. Still, this argument only argues against a coming bear market rather than making a positive case for equities. How likely is the economy to avoid recession over the next 3, 7 or 10 years? I have no idea. But this forecast is critical to the case being made here.

Additionally, it seems like the past couple of recessions may have been triggered by major asset price declines as much as anything rather than the reverse. If this is true, then waiting for a recession to tell you when to get out of stocks is likely to be a losing proposition.

As for the hyper-inflationary case, this is sort of a spin on the familiar “this time is different” argument for owning stocks. While it may be an interesting exercise to think about these sort of possibilities, we really have no reason to believe that the Fed is likely to pursue policies that would create and sustain hyper-inflation. In fact, history shows the Fed would do everything in its power to avoid hyperinflation.

Finally, in regard to the Santa Claus analogy, this sort of reminds me of Pascal’s Wager. From Wikipedia:

Pascal’s Wager is an argument in apologetic philosophy devised by the seventeenth-century French philosopher, mathematician and physicist Blaise Pascal (1623–62). It posits that humans all bet with their lives either that God exists or not. Given the possibility that God actually does exist and assuming an infinite gain or loss associated with belief or unbelief in said God (as represented by an eternity in heaven or hell), a rational person should live as though God exists and seek to believe in God. If God does not actually exist, such a person will have only a finite loss (some pleasures, luxury, etc.).

Applying this idea to investors, bulls may posit that ‘given the possibility that an omnipotent Fed does exist and assuming an infinite gain or loss associated with belief or unbelief in said Fed, a rational person should live as though an omnipotent Fed exists. If it does not actually exist, such a person will have only a finite loss.’ This may be the ultimate “this time is different” argument. The Fed has never been, nor will it ever be omnipotent. Still, I think this begins to explain how some investors view the market these days.

But the analogy also brings up another point which is a critical insight into current market psychology: So long as we collectively believe the Fed is omnipotent then we will continue to receive the benefits of their magnanimous policies. As soon as we begin to doubt the Fed’s powers, the confidence game is up and we can no longer expect those gifts under the tree at the open of trading every day.

I think this is very close to what’s going on in the minds of many investors today. While I find the Santa Claus argument lacking in terms of making a convincing case for stocks outperforming the risk-free rate, I think it does a fantastic job of explaining why investors feel they should be bullish right now.

I received a few other responses but nothing that met my simple criteria. The lack of convincing arguments is either due to the fact that there just isn’t a compelling case to be made or I have just cultivated the sort of audience that doesn’t believe in Santa Claus. Either way, I still think it’s very difficult to justify owning risk assets once they have become priced so high as to virtually guarantee they underperform riskless ones. If you disagree and have a convincing case for me, I’m all ears.