Yesterday morning I came across a piece over at Harvard Business Review titled, “To Make Better Decisions, Combine Datasets.” I began reading it and realized that’s exactly the key to investment success and what I’ve tried to do with my market timing model: combine a variety of predictive datasets to create a holistic forecasting and timing model.

The stock market is driven not just by fundamentals or sentiment or technicals alone but by all of them in concert with one another. It follows then that an investor should try to incorporate each of them into her investment process in order to maximize its effectiveness.

And this is where I think many investors get lost. They try to focus on only one of these three. Fundamentals alone may work over the long run but cheap stocks can always get much cheaper in the short-term or they could just be cheap for a very good reason (I’ve learned this lesson more than a few times). Sentiment can also be very helpful but the crowd isn’t always wrong and markets can ‘stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.’ And, as many traders know, the ‘trend is only your friend until it comes to an end.’

What I’ve found in my 20+ years of observing and trading markets is that looking at the forest, by putting all of these together, rather than the trees alone is absolutely crucial to making good decisions. So I thought it might be fun to look at the individual components of the model to see not only what they are saying about the markets but how they might be misleading when taken on their own.

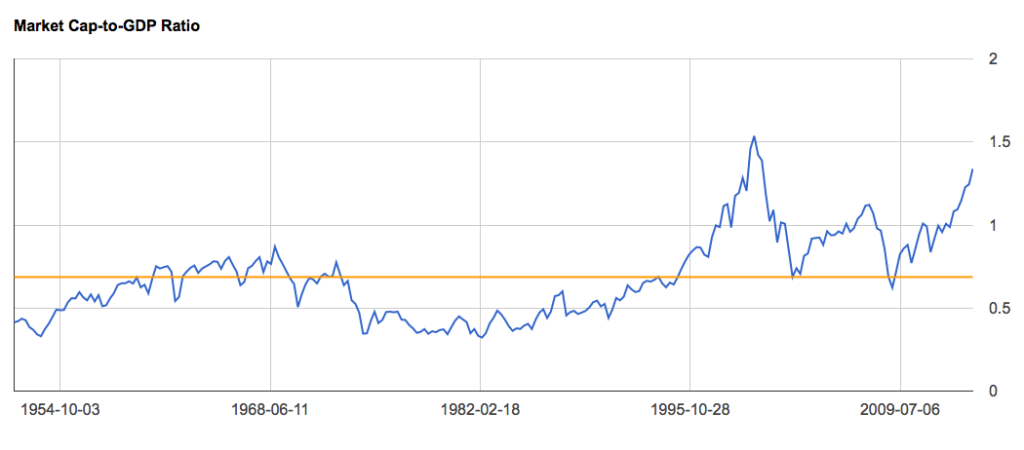

For my fundamental component I use Buffett’s favorite valuation yardstick, total market capitalization-to-GDP. On its own it has roughly an 83% negative correlation with future 10-year returns in the stock market (based on 65 years worth of data). This means higher levels for this indicator are correlated with lower future returns and vice versa. Here’s what it looks like over the past 65 years or so:

Even considering the fact that the internet bubble has pushed the average higher over the past ten or fifteen years, this measure still suggests stocks are priced significantly above their historical range. Based on its high correlation with future returns this suggests investors should expect a very low return from present levels over the next decade.

Even considering the fact that the internet bubble has pushed the average higher over the past ten or fifteen years, this measure still suggests stocks are priced significantly above their historical range. Based on its high correlation with future returns this suggests investors should expect a very low return from present levels over the next decade.

BUT… this has been the case for most of the past 20 years! An investor looking at this measure alone might have sat out a couple of major bear markets but also would have missed a couple of the most massive bull markets in history! So it’s probably not smart to use this measure in isolation. Adding other related asset classes (like bonds – we’ll come back to that) and other, unrelated indicators should help give a bit more clarity.

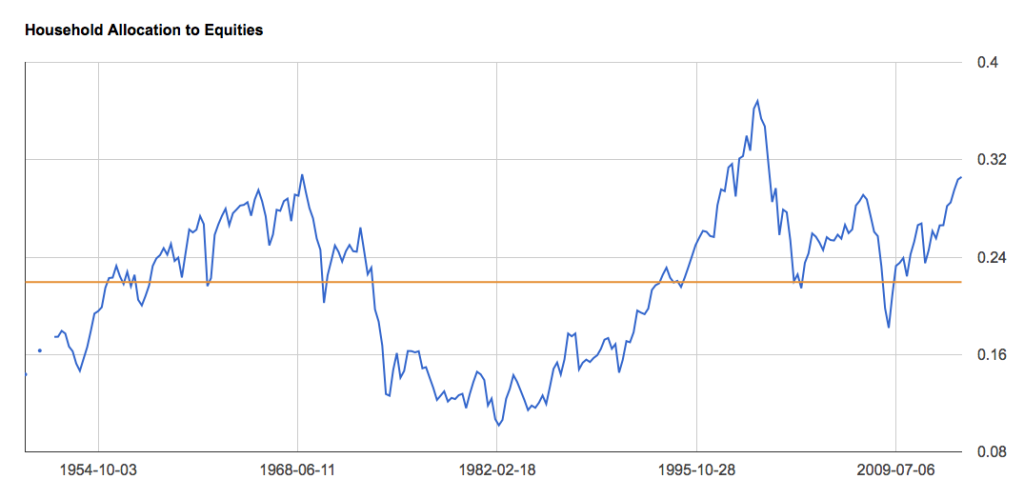

My sentiment measure tracks the percent of household financial assets invested in equities. Believe it or not this measure is even more highly negatively correlated with future returns than Buffett’s valuation measure above (closer to 90% – hat tip, Jesse Livermore). Here’s what it looks like over the same time frame:

It’s also currently sitting significantly above its long run average suggesting returns should be far below average going forward. As I mentioned this is a better forecasting mechanism than the fundamental measure but even if the incredible euphoria of the internet bubble got you out of the stock market you may not have gotten back in over the past 15 years because we haven’t seen anything like the pessimism witnessed at the 1982 low.

It’s also currently sitting significantly above its long run average suggesting returns should be far below average going forward. As I mentioned this is a better forecasting mechanism than the fundamental measure but even if the incredible euphoria of the internet bubble got you out of the stock market you may not have gotten back in over the past 15 years because we haven’t seen anything like the pessimism witnessed at the 1982 low.

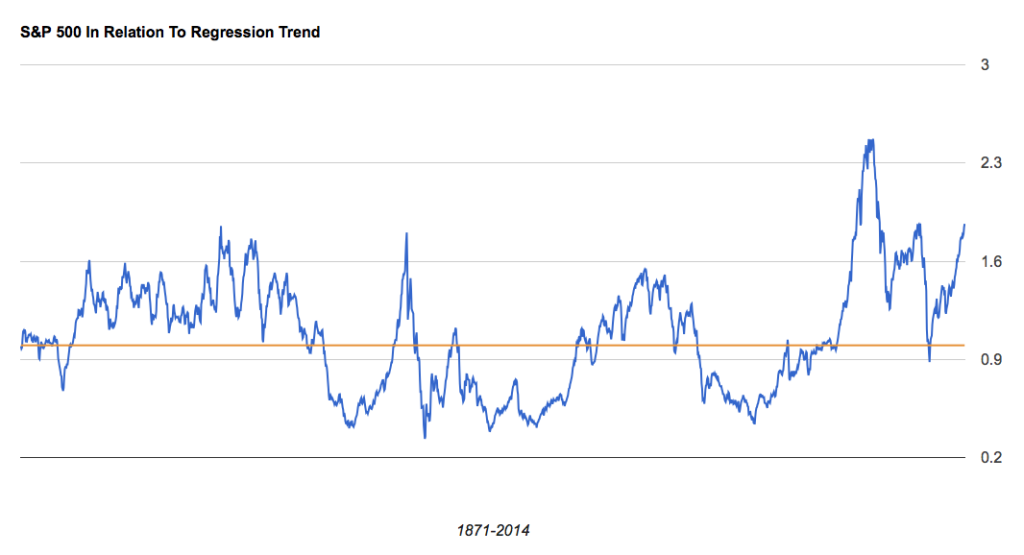

Finally, I’ve added a third component to the model, inspired by Doug Short: a simple trend regression model based on Robert Shiller’s data going back nearly 150 years. With a negative correlation of roughly 74%, it’s not quite as effective at forecasting future returns as these other two but I think adding it, as a third independent component based on a very long-term trend, helps to make the model more robust. So here’s what the S&P 500 looks like relative to a regression trend line over the full time period:

Once again this indicator shows the stock market to be trading very close to the top of its historical range. Still, like the fundamental model this one might have had you sitting out of the stock market for perhaps the past 20 years!

Once again this indicator shows the stock market to be trading very close to the top of its historical range. Still, like the fundamental model this one might have had you sitting out of the stock market for perhaps the past 20 years!

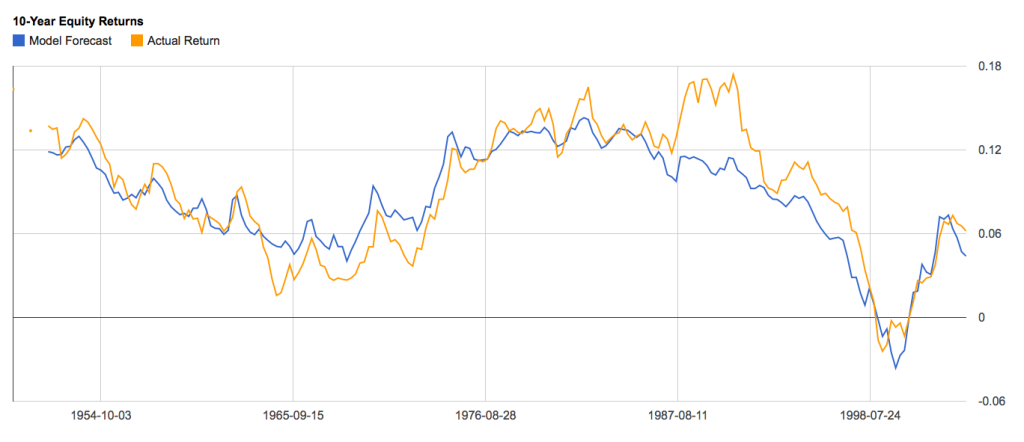

So even though we have three independent models we need a way to put them together and then to put them into some sort of context. What I’ve done is used each indicator individually to create a 10-year forecasting model. Then I’ve simply averaged them together each quarter. All told, the combination results in a correlation to future 10-year returns of about 90%. Here’s a chart of the model’s forecast returns as compared to actual 10-year returns for the stock market:

Where the model is farthest off the mark (where you see the yellow line far above the blue line) is in the late 80’s early 90’s. Stocks surged further and faster during the internet bubble than the model forecast they would. Removing those years, the model’s correlation value rises to about 94%.

Where the model is farthest off the mark (where you see the yellow line far above the blue line) is in the late 80’s early 90’s. Stocks surged further and faster during the internet bubble than the model forecast they would. Removing those years, the model’s correlation value rises to about 94%.

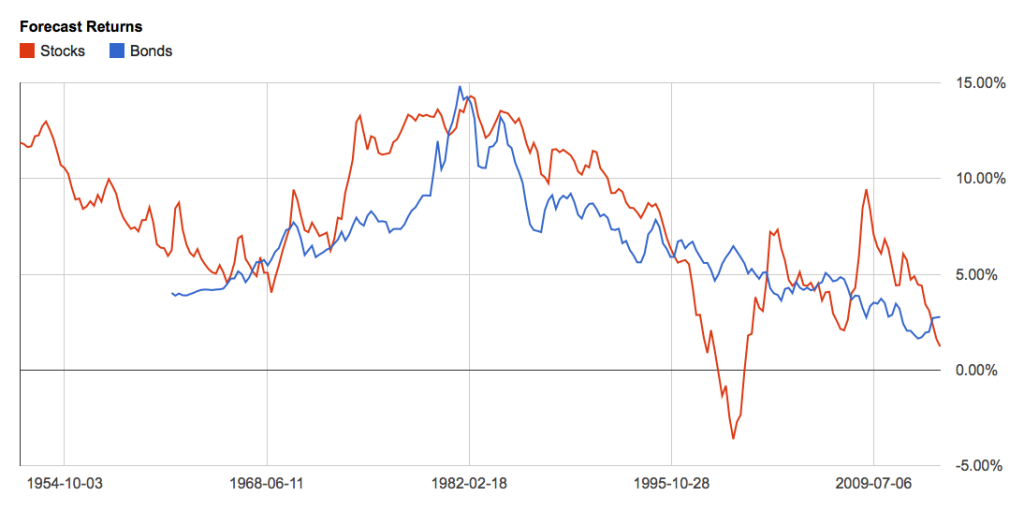

So we know what the individual readings look like. What’s the model saying about future returns from here? As the chart below shows, the model forecasts a return of just 1.2% per year over the next decade:

To add some context, in addition to the 10-year forecast I’ve put the yield of the 10-year treasury note on the chart, as well. Investors don’t look at potential returns in a vacuum; they compare potential returns of different opportunities, many times looking at the “risk-free” rate of treasury notes in the process. This next chart shows the difference between the model’s forecast return and the yield on the 10-year treasury note:

To add some context, in addition to the 10-year forecast I’ve put the yield of the 10-year treasury note on the chart, as well. Investors don’t look at potential returns in a vacuum; they compare potential returns of different opportunities, many times looking at the “risk-free” rate of treasury notes in the process. This next chart shows the difference between the model’s forecast return and the yield on the 10-year treasury note:

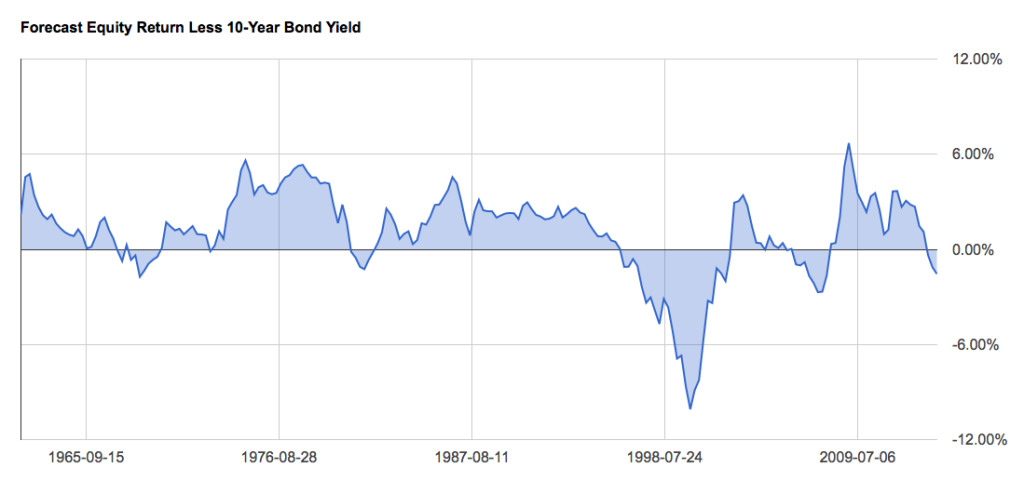

When the blue line is above zero, stocks offer the better return; when it’s below, bonds do. And as I’ve shown before in “How To Time The Market Like Warren Buffett” this timing model works very well. Just buy whatever asset class is more attractive – trading only once per year – and you’ll kill a buy-and-hold approach.

When the blue line is above zero, stocks offer the better return; when it’s below, bonds do. And as I’ve shown before in “How To Time The Market Like Warren Buffett” this timing model works very well. Just buy whatever asset class is more attractive – trading only once per year – and you’ll kill a buy-and-hold approach.

I think this alone is validation of a multi-disciplinary approach. But adding one more super-simple component makes it that much more effective: before we go and sell our stocks because bonds are more attractive, we want to make sure we don’t sell too early in a bull market or buy to early in a bear market. As the chart above shows this model would have had you sell your stocks and shift into bonds all the way back in April of 1996 and then miss all the gains of the next 3 1/2 years.

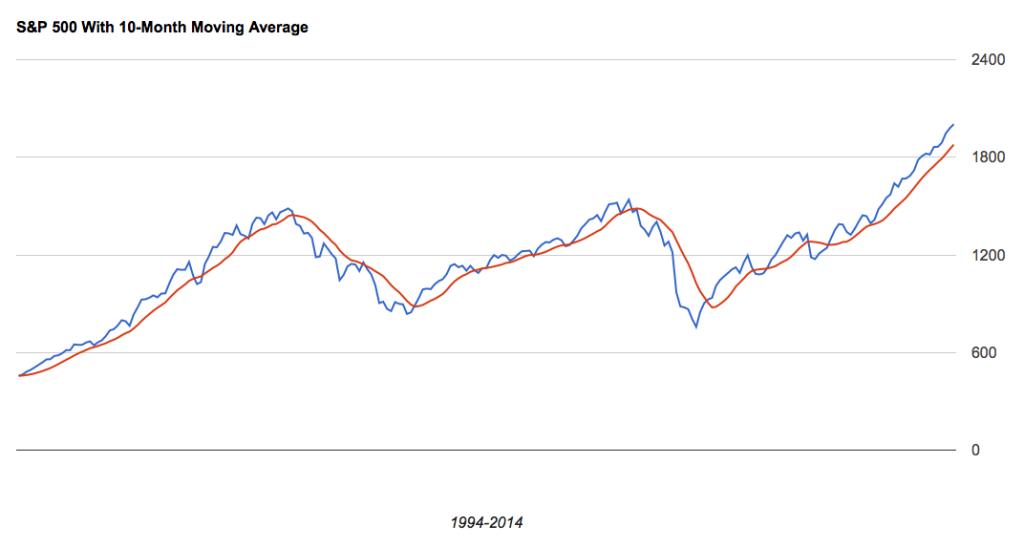

Adding a very simple trend-following approach solves this problem (hat tip, Meb Faber). Rather than sell right when bonds become more attractive it’s much more advantageous to wait for the trend to end. And as a representation of the trend, we can simply use a 10-month moving average. Below is a chart of the S&P 500 and this moving average:

To be clear we’re not trend followers all the time with this model. We buy-and-hold until the model tells us that stocks are not attractively priced and then we become pure trend followers. Once the model tells us stocks have become less attractive than bonds we wait for the S&P 500 to close at least 1% below its 10-month moving average at which point we sell our stocks and sit in cash, buy bonds or even short stocks (the latter generates the best returns over the period studied).

To be clear we’re not trend followers all the time with this model. We buy-and-hold until the model tells us that stocks are not attractively priced and then we become pure trend followers. Once the model tells us stocks have become less attractive than bonds we wait for the S&P 500 to close at least 1% below its 10-month moving average at which point we sell our stocks and sit in cash, buy bonds or even short stocks (the latter generates the best returns over the period studied).

Should the index at any point close back above its 10-month moving average by at least 1% we buy stocks again. Like I said, so long as stocks are less attractive than bonds we are pure trend followers. Only when the model suggests stocks are once again more attractively priced than bonds AND the trend has turned up (as indicated by a monthly close above the 10-ma) do we buy stocks and abandon trend-following for buy-and-hold.

Ultimately what this produces is a combination buy-and-hold/trend-following model that owns stocks roughly 80% of the time and seeks to avoid major bear markets precipitated by high valuations, high levels of bullishness and prices extended far above their regression trend. It doesn’t avoid losses entirely, though.

The model didn’t recommend a move out of stocks prior to the 1987 crash which resulted in a decline of roughly 26% (its largest drawdown). It did, however manage to avoid the ’73-’74, ’00-’02 and ’08-’09 bear markets, the latter producing about a 50% decline. In fact, this is where all of the model’s outperformance is generated: in recognizing these major turning points fairly early on – essentially giving a warning signal – and then switching from buy-and-hold to trend-following when that strategy is more effective.

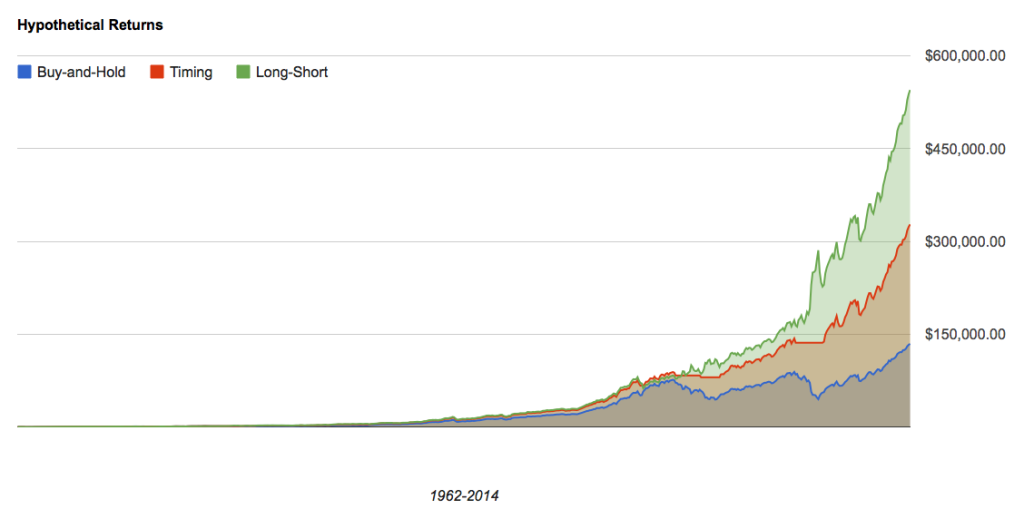

The next chart shows the results of three different investors. The first is a simple buy-and-hold strategy (blue line). The second goes to cash when the model indicates (red). The third, rather than going to cash, shorts the index (green):

Clearly there is significant benefit to abandoning buy-and-hold for a trend-following approach when our model suggests stocks are unattractively priced. Over the period the investor who just sits out major bear markets in cash ends up with twice as much as the investor who holds through the entire decline. And the investor who gets short, in turn, fares far better still.

Clearly there is significant benefit to abandoning buy-and-hold for a trend-following approach when our model suggests stocks are unattractively priced. Over the period the investor who just sits out major bear markets in cash ends up with twice as much as the investor who holds through the entire decline. And the investor who gets short, in turn, fares far better still.

I truly believe these superb results, hypothetical though they be, can be attributed to the holistic nature of the model. It combines datasets that are valuable independent of one another into something greater than its parts.

As of now, the model is telling us that stocks have once again become unattractive relative to bonds. However, the uptrend is still in tact. So it’s probably valid to be bearish for fundamental, sentiment and regression reasons. But the trend is also a valid reason to be bullish – even if it is the only reason. So I’m still looking at the market through a bearish lens right now but I’ll be watching for a monthly close at least 1% below the index’s 10-month moving average for the trend to validate the fundamentals and sentiment.

For reference I’ve put up all the spreadsheets, calculations and charts I used on a public Google Drive sheet here: Market Timing Model. I’ll be updating it as new data comes in.

Finally, I need to make the same disclaimer I’ve made over and over again during this series: because this is a hypothetical model that doesn’t incorporate taxes, transaction fees, etc. it is not representative of any real returns. It is merely for educational purposes. Clearly, past performance may not be indicative of any future results.