Below are some of the most interesting things I came across this week. Click here to subscribe to our free weekly newsletter and get this post delivered to your inbox each Saturday morning.

LINK

Last week, I explored why investors should mind the “Kindleberger Gap.” This week, theme continues with a piece from Martin Wolf who writes, “Kindleberger argued that the stability of an open world economy depended on the existence of a hegemonic power willing and able to provide essential public goods. But… what if the hegemon undermines its own fiscal and monetary stability?”

CHART

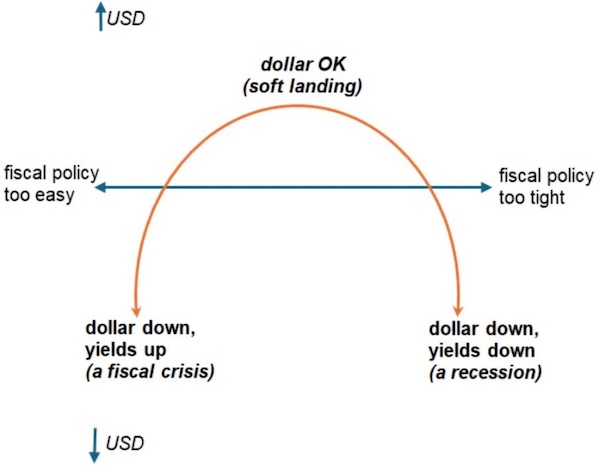

Potentially reaching the limits of fiscal and monetary capacity threatens to turn the so-called “dollar smile” upside down. “A dollar fiscal frown is the best way to picture things. On the left is a fiscal stance that is too easy. This leads to a combined drop in US bonds and the dollar… On the right is a fiscal stance that tightens too quickly, closing the deficit sharply but forcing the US into a recession and a deep Fed easing cycle,” writes George Saravelos.

LINK

Currently, we appear to be testing the left side of the smile. Adding to this threat to the bond market is the impact from deglobalization. As Joe Weisenthal points out, “You get a greater investment impulse (for self sufficiency reasons) and a diminished capacity to efficiently deploy that spending (because of trade barriers). And voila, there’s your recipe for a more inflationary environment.”

LINK

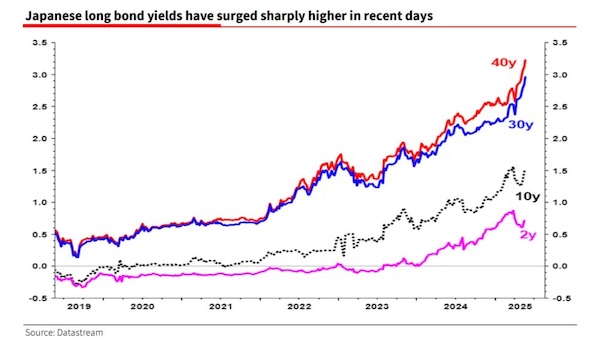

And it’s not just the U.S. dealing with the consequences of pushing the limits of fiscal and monetary largesse. Japanese bond vigilantes may be even more eager to deal out punishment than their counterparts stateside. Yet, as Albert Edwards points out, Japan historically leads the rest of the world in these sorts episodes. “If sharply higher JGB yields entice Japanese investors to return home, the unwinding of the carry trade could cause a loud sucking sound in US financial assets.”

QUOTE

Few seem too concerned about this possibility right now. “Stock markets have rebounded even though historically-high tariffs still apply for most countries trading with the U.S. ‘It’s an extraordinary amount of complacency,’ Dimon said, noting that the last time the country saw 10% tariffs on all trading partners was 1971,” reports The Wall Street Journal. That, of course, was just the start of a “lost decade” for the stock market.