“In my opinion, you have to be wildly optimistic to believe that corporate profits as a percent of GDP can, for any sustained period, hold much above 6%. One thing keeping the percentage down will be competition, which is alive and well. In addition, there’s a public-policy point: If corporate investors, in aggregate, are going to eat an ever-growing portion of the American economic pie, some other group will have to settle for a smaller portion. That would justifiably raise political problems–and in my view a major reslicing of the pie just isn’t going to happen.” –Warren Buffett, November 1999

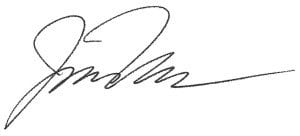

Twenty years after this was written, the wild optimists have been proven right and Buffett’s faith in reversion to the mean proven wrong. Corporate profits as a percent of GDP soared above 6% in the first quarter of 2002 and, outside of a brief dip during the fourth quarter of 2008, have remained above that lofty mark for nearly two decades now.

Competition, it turned out, was not, in fact, alive and well, as Bridgewater wrote last year. Antitrust policy has been loosened to the point at which many firms have been able to buy up their rivals and create oligopolies if not duopolies or monopolies across a number of industries. Globalization (and demographics) certainly played a part, as well, but there is one other cause that I think fails to garner the attention it deserves.

Monetary policy over the past couple of decades has also shifted toward aggressively and directly supporting capital. It’s true that the Fed doesn’t really have the tools to support labor directly. While part of its dual mandate is to promote full employment, it can only do this through the capital markets by lowering interest rates and buying up securities. In this way, extreme monetary policy is the ultimate in “trickle down economics,” the idea that when the wealthy benefit inordinately their spending and investment will eventually benefit everyone else. The results, however, speak for themselves.

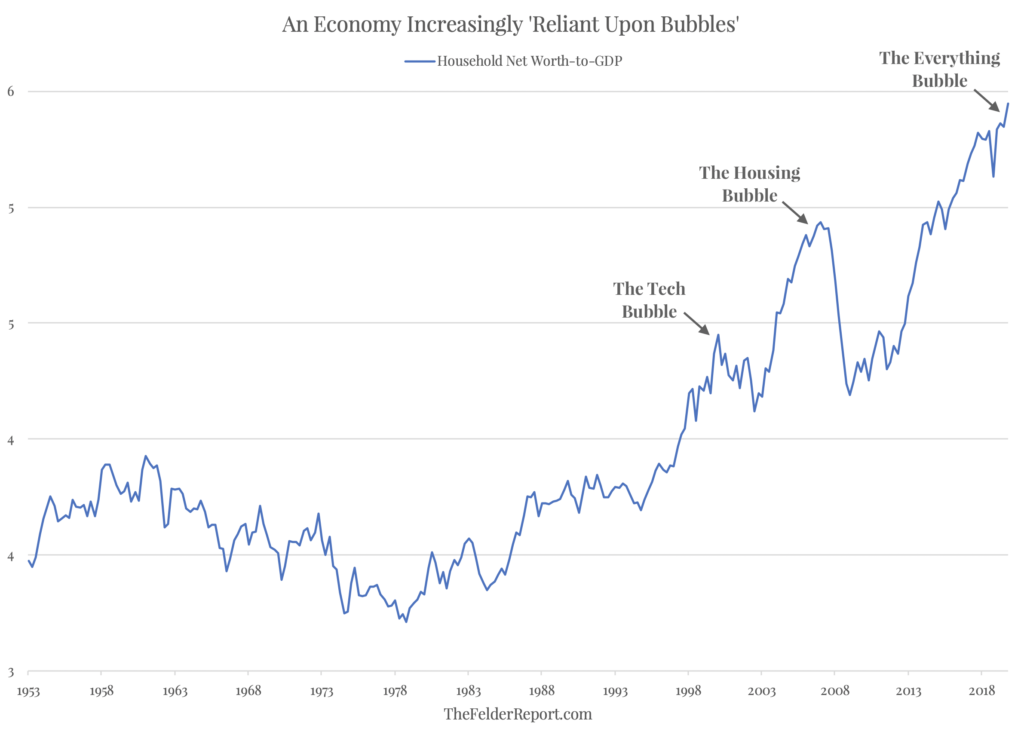

Explicitly targeting “wealth effects” over the past two decades (first the housing bubble under Alan Greenspan and then the everything bubble under Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen), the Fed has pushed household net worth as a percent of GDP to record heights. Capital has benefitted to a degree never seen before in our nation. Meanwhile, labor share of income has fallen to its lowest levels in history and wealth inequality is very possibly even greater than it was a century ago.

Where Buffett got his prediction right is in the political problems he foresaw. Both political parties are moving to the extremes, conservatives toward nationalism and liberals towards socialism. This is an inevitable outcome of the “major replacing of the pie” we have seen over the past 20 years. And it will eventually lead to another reslicing that is more equitable.

The backlash against wealth and income inequality and the fallout of the pandemic are the driving forces behind the trends already moving towards a renewed antitrust framework and a rethink of globalization and the offshoring of critical production. However, while these are important areas to focus on, we should not forget to include the most powerful institution on the planet and its own policies that have done at least as much to dramatically skew the economy and the financial markets.

Extreme monetary policy has not only artificially inflated capital but has also greatly exacerbated the boom bust cycle, leading to two once-in-a-generation economic crises in just over a decade. Inflating asset prices and encouraging increasing indebtedness beyond what the natural economic cycle can support is not a sustainable way of trying to manage the economy. Even former Fed Chair Janet Yellen lamented after the financial crisis, “Somehow we need to go to an economy that is using its resources, operating at full employment, but doing so in a way that isn’t reliant on bubbles.” The economy has only become far more dependent upon bubbles in the capital markets since then.

So for those looking for ways to level the playing field that has been tilted greatly in favor of capital over labor, I would humbly suggest they include the Federal Reserve and its role in exacerbating the underlying problems. Without a holistic approach that includes a rethink of extreme monetary policy, any proposed solutions may only prove to be half measures.