Most people have a hard time thinking about risk. They usually just take their recent experience and extrapolate it out indefinitely into the future:

‘Stocks have gone up over the past few years so they’ll probably continue to do so. We had a 10% correction recently so we should be prepared for that sort of thing to happen again but there’s no reason to believe a bear market is lurking.’

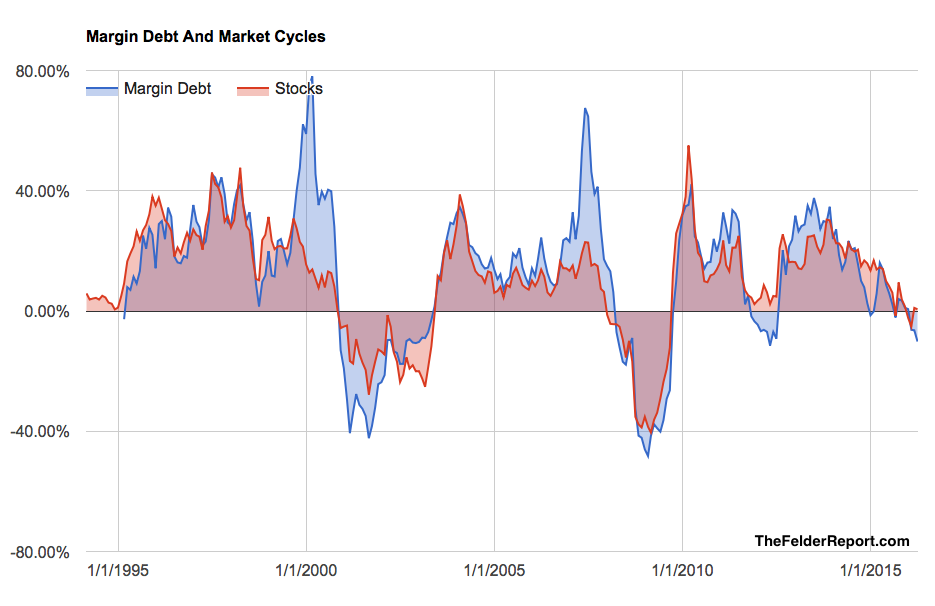

What makes risk hard to think about is that it remains latent the vast majority of the time, even while it continues to grow. But just because it remains hidden doesn’t mean it’s not real. And this is really my point with regards to margin debt. Because it hasn’t been a problem in many years, most people shrug it off as not being a risk in and of itself. However, I believe there is sufficient evidence to suggest margin debt, especially when measured in terms of GDP, can be a great indicator of potential supply and demand for stocks and thus risk.

When margin debt has been low it’s been a terrific sign that potential demand, or buying power, for stocks is great and investors should be more greedy. Conversely, when margin debt has been very high it’s been a terrific sign that potential demand is very low and investors should be more fearful. More to the point, at recent extremes, it has signaled a great deal of potential supply. In other words, margin debt clearly signaled during these occasions there was heightened risk of a stock market crash precipitated by forced selling.

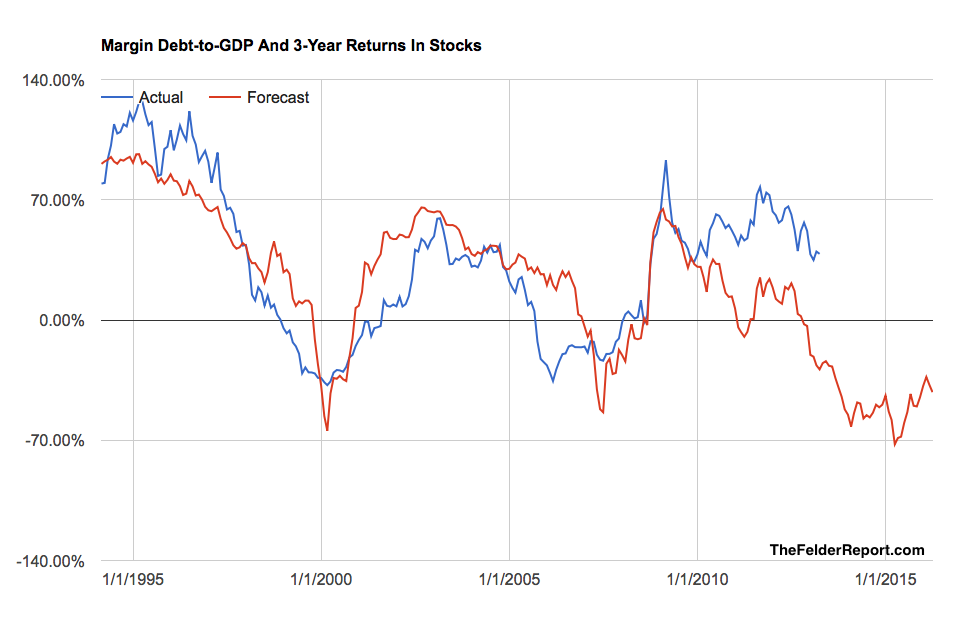

The chart below plots margin debt-to-GDP (inverted) against 3-year returns in the stock market. Notice that at the 2000 and 2007 stock market peaks, this measure suggested returns going forward would be lousy. The massive forced selling that occurred during the bear markets that followed those episodes ensured that they were. You’ll also notice that at the 2003 and 2009 lows, it suggested forward returns would be fantastic. The massive buying power unleashed during the bull runs that followed those episodes ensured that would also prove true.

Margin debt today is at an extreme that suggests forced selling could become a problem once again. But the real question is, ‘what will cause this latent risk to materialize?’ This is really a chicken or egg sort of question. Is it a bear market that precipitates forced selling or does forced selling precipitate a bear market? I don’t think we can answer that one.

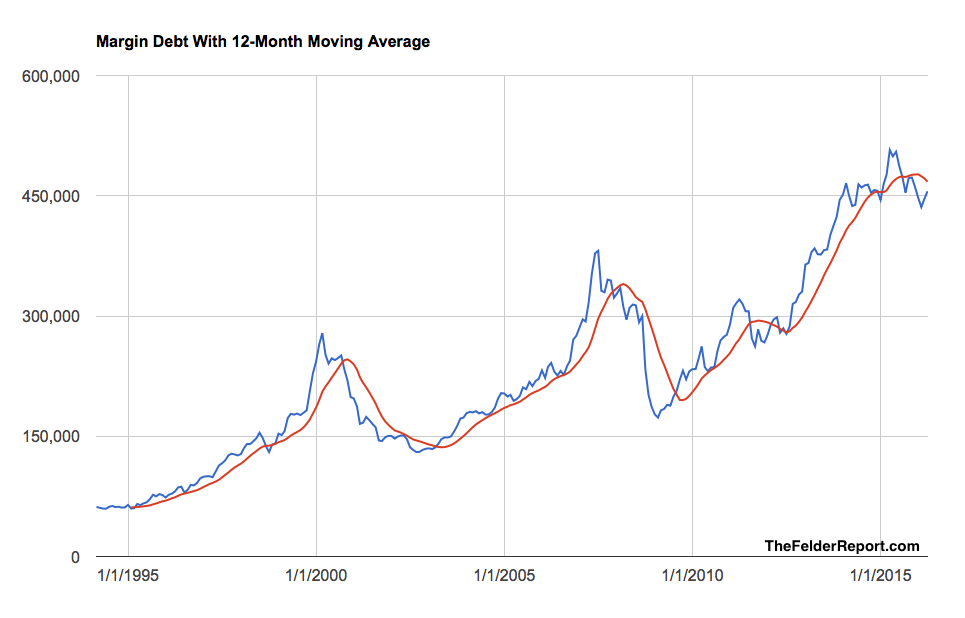

What we do know is that margin debt is now falling from the most extreme level seen during our lifetimes, both in absolute and relative terms. And it’s falling at a rate rarely seen outside of a bear market. Because the trend in margin debt has now reversed to the downside and from such an extreme, this latent risk is something we should probably pay especially close attention to right now. Any further selling in the stock market could more easily turn the virtuous cycle of borrowing to buy, pushing prices higher enabling more borrowing to buy, into a vicious cycle of forced selling to pay down debt which pushes prices lower creating more forced selling.

The bottom line is this: Margin debt shows investors have recently become extremely greedy. As a result, investors would do well to heed Warren Buffett’s famous advice and become more fearful. In the past, margin debt has been a very good indicator of what to expect in terms of the magnitude of a potential bull market rally or potential bear market decline. Right now it suggests that, if we are in the midst of a new bear market, it is likely to be one of the more painful ones we have ever seen, simply as a result of the record amount of potential forced selling.